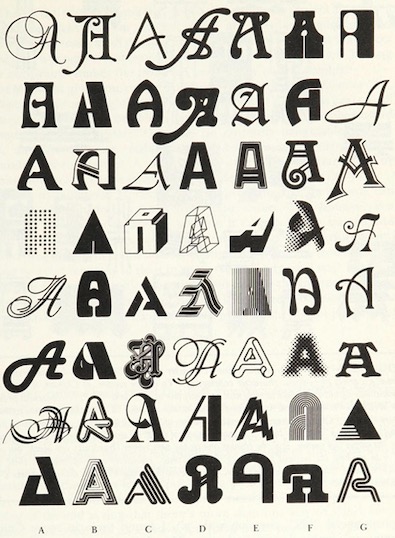

emphasis | ˈɛmfəsɪs | noun (plural emphases | ˈɛmfəsiːz | ) [mass noun]

1 special importance, value, or prominence given to something: they placed great emphasis on the individual’s freedom | [count noun] : different emphases and viewpoints

2 stress given to a word or words when speaking to indicate particular importance: inflection and emphasis can change the meaning of what is said

• vigour or intensity of expression: he spoke with emphasis and with complete conviction

Emphasis on something means that we want to highlight it from the rest. A common way to do this in text is to italicize or give a boldface or even underline the text. At times colour is added to text to highlight it or colour is added to the background of the text. All these elements of typography work when there is a common background against which these elements standout. Hence emphasise the words as required. But,

If everything is emphasised, the un-emphasised becomes emphasised.

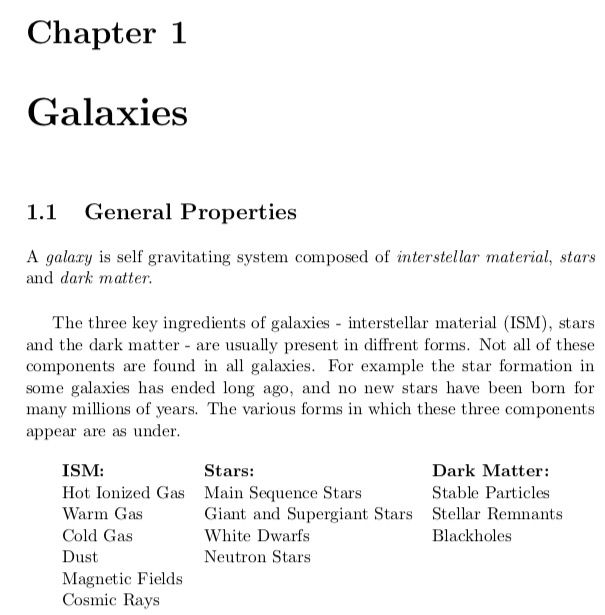

But consider a block of text which is completely emphasised.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Thus we see that the appeal of the emphasis is lost! The only way emphasis will work is to create a background against which it stands out. Let us return to our examples above

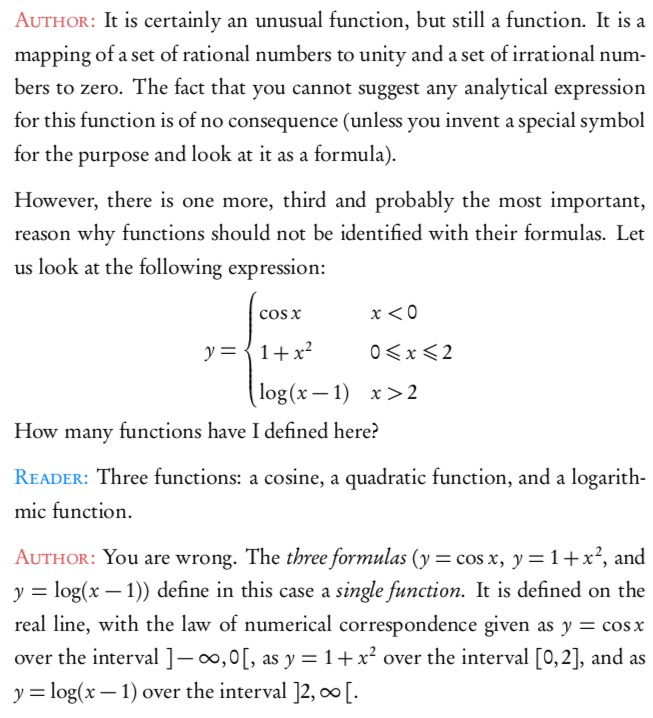

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

For me, personally I have not used underline or the highlight. And recently have shifted to coloured italics as my choice of emphasis.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Sometimes this produces very pretty results (at least I am very happy about them 🙂

(ETBB font with OrangeRed (#FF4500) italics )

In some cases boldface colour also gives very good results:

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Further reading:

Elements of Typographic Style by Robert Bringhurst