The Plan

To ride to Pune [पुणे] and get the registration of WindWolf done on the same day.

This was something long overdue. I had to ride to Pune to get the registration of WindWolf done again. The validity of the registration was till 18th May 2008. When the date was written on the RC book [is it not a wrong nomenclature Registration Certificate Book?] five years ago, I thought this date was long in the future. Even now it is hard to believe that WindWolf has become a part of my life from last five years. It has been five years she has been with me! Now its almost impossible to think life without her…

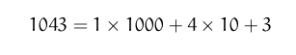

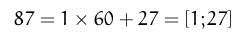

The RC Book Cover

The Doom Day: 18/5/2008

Any way when that dreaded date became a reality, that the validity of the registration certificate for WindWolf would be over on the 18th. We missed one opportunity to ride to Pune, as the Insurance papers were missing. But thats another story….

Now the missing papers were found, and the time to the deadline was approaching, this ride was a must. So here we go. We ride for Pune on the 15th of May.

The Ride

The plan was to ride early in the morning, when the sun has yet to rise [Does it really everyday?]. Since it is summer, I did not want to face the sun when riding. So anyways the ride begins at 5:10 am. I had put on a jacket and gloves just in case, but they did prove to be useful Who says you do not need them in the summers?

Riding early in the dark gives you pleasures that you cannot get in the daylight. When you are alone for quite some distance; so to speak that there are no vehicles with their headlights on for quite some distance, the reflectors give you an awesome view. When you ride on the road with your headlights on, and there is no one else, the reflectors shine just for you. So your bike makes you feel special. You feel like as if you are The King of The Road. Just as you turn the beam of the headlight, the different reflectors just light up in the areas which were just a moment before completely dark. The path is made by you and it is made for you. You must be feeling like you are on an air strip, trying to land a plane [though I do not know what pilots feel!]. This is another thing that has to be felt, and cannot be understood only in the words, the feeling runs much deeper, much deeper than the words can dwell. Maybe this is the feeling The reflectors on the road light up till very far away, so that you get an effect of road going far, far away from you…

The petrol was not enough and we did hit the reserve just after Vashi [वाशी]. So had to fill in at the first pump. But did fill it in at the second one as the first one was exclusively for diesel vehicles.

With the petrol filled in we rolled on the highway. I used the JNPT [Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust] exit for leaving Panvel [पनवेल], which was discovered by me and Ritesh in a hard way while going to Karnala [कर्नाळा] last year.

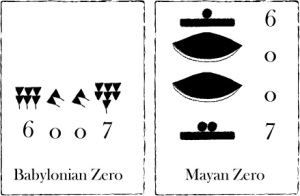

Windwolf and Damitr: The incredible duo.

I prefer this way because the traffic is very less as compared to the way through Panvel. From the ‘T’ point where the right way goes towards JNPT and the left one goes towards Goa and Pune.

Here after the Panvel exit, the patch before the crossing of the Mumbai-Pune Expressway, the once [in]famous dance bars come into view. Thanks to R. R. Patil, they have lost their old glory now, but their neon signs glow even now. There is still some fire left in the ashes, will they rise one day again? All along the way till Panvel there was smog in the lower parts, this maybe partly due to the brick ovens, or the factories that are in the Navi Mumbai [नवी मुबंई] area. The presence of smog gives a surreal look to the entire landscape. At one point there was a lot of free space, in which there were some sparse trees. All you could see was the trees and their tops, most of the ground was covered with smog. So the scene looked as if the trees were growing in clouds instead of land…

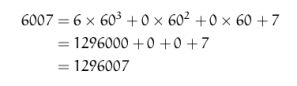

Panvel from the JNPT bypass ‘T’ point early in the morning, looks as if it is sleeping cozily in the blankets of smog. Here I saw one very prominent feature of the mountain visible from Panvel, which I missed during all my last rides. This is Prabalgad [प्रबळगड]. Its peak looks impressive and is asking to be climbed…

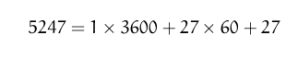

Panvel in the morning haze, with Prabalgad in foreground, notice the clouds far away, they do look like mountains.

Prabalgad.

The weather was very fine. The cold wind kisses you on the cheeks and leaves you with a pleasant and warm feeling. The extra sheath of insulation was almost perfect for the kind of weather I was riding into. Another thing about riding in the dark, as the time goes by, the color of the sky changes gradually. The gradients of colors are amazing and cannot be described in words they have to be seen. There are things about riding which you cannot capture in words, but only can be experienced, so time and again I am referring to this feeling of being felt. [If you have not read Robert Pisrig’s Zen And The Art Of Motorcycle Maintenance maybe you should.] For each phase before the dawn, there are different shades which are dominant. And if, the sky has some clouds, the colors and clouds can play amazing tricks on you. If the road is winding you see clouds in different directions, in different shades, shapes and sizes. Also if the sun is behind the mountains, it gives rise to spectacular silhouettes of the mountain; the mountain is dark black and the sky appears in shades of orange and red. In the background of the mountain range, the distant clouds at a particular time appear themselves as mountains. At the horizon you cannot distinguish between the lines of distant mountain ranges and the array of clouds present beyond them. They appear so similar, that it is hard to tell them apart. But as the sun rises on the sky they become more demarcated, and they just dissolve. Many of them become thinner and then ultimately melt away…

Another thing about riding the bike that thrills me is that the silence that you get with it. When you are riding alone, you are alone. There are no other sounds, except that of the firing of the engine and the voices of yourself that you hear in the head. The riding on the bike gives you a solitude, which is so difficult to get with the lifestyle that we have adapted. This is a aloneness in which you can engage in a dialogue with yourself. I am saying dialogue with oneself, not a monologue; because many times I ask myself questions as somebody else, and answer the questions as somebody else. Some times is it the other way round? And I tend to forget myself in all this? Anywhere where am I? [See interesting and highly readable articles about “I“ in Douglas Hofstadter and Daniel Dennet’s Mind’s I]

Since it is summer, and the spring is almost finished, the trees on the sides of the road greet you with their new and tender leaves. This is a different shade of green, which has its own charms. The green leaves, against the start blue background of the sky mark the summer and spring for me. This marks completion of another cycle for them. Here is a

summer time song that I liked and echoes many of my feelings…

After Khopoli [खोपोली], the real climb begins. There is an Electric Power Station, run by the Tata’s, also there is the residential colony till half part of the climb. Just near the colony there is a very sexy curve, which sets the adrenaline up by many levels. O! I just can’t describe the feeling….

Windwolf in The Ghat.

After many windings on the road we finally touch upon the familiar yellow and blue bands which declare that now you are riding the Mumbai-Pune Expressway. Here two wheelers and three wheelers are not allowed, and so are tractors and pedestrians not. After riding a little on the expressway, we get down at the Lonavala exit. The sun is quite high up now as compared to the time of the day. Anyway, now the scene created is interesting. As I am riding eastwards I face the rising sun, and it feels like summer, while in both the rear view mirrors I could see dark gray clouds rising. So these two were two entirely different world. One was the future, and one was the present, that of the forthcoming monsoon’s and that of the present summer. It was feeling as if the clouds were following you in the time, I felt as if I was the harbinger of the monsoons which will hit in the coming two weeks [The

IMD website claims June 10 is the time it will hit Mumbai]…

You can see some photos from a ride last year

here.

By the time I reach Deccan plateau [दख्खनचे पठार] the sun is quite high, but the wind temperature is still low. Now the local road traffic beings to emerge, but sill is quite low. Near the Bhaje [भाजे लेण्या] caves, I can see the twin forts of Visapur [विसापुर] and Lohagad [लोहगड] still immersed in clouds. They are a sight to watch and trek in the Monsoons. I have done one and a half treks of Visapur fort. Both during the monsoons. I say half because that trek had to be abandoned midway, due to “footware” problems of a six foot hobbit ;). Lohagad I have trekked thrice and not one time in the monsoons.

At 7:30 I had crossed Kamshet [कामशेट] and by 8:00 am I was riding happily in Wakad [वाकड]. They are making a fly-over there, good less jams. I was all happy for this wonderful ride and thought that this will never come to an end. The joy of riding was with me. But ….

As soon as I departed from the highway at the Hinjewadi [हिंजवाडी] junction, the ugly, chaotic, mean, non-rational, messy, unregulated traffic of Pune was attacking me, complimented by the pathetic and distressed conditions of the roads. It took me just over 20 minutes to reach IUCAA from Hinjewadi, but this was the worst part of the ride. UGhhhhh……..

There was dust in my eyes and they became sore. People here don’t respect traffic laws, everyone makes the rules, where all are equal, but they themselves are more equal than the others. So be it. If there is a demise of Pune as a city, the chaos of the roads and one that is on the roads will be one of the biggest reasons for sure. But let go prophecies and we are back to the reality that it was a nightmarish thing after such a wonderful time I had

with her.

I reached IUCAA at Sam’s place at 8:25, which means that we reached here in about 3 hrs 15 mins, have to improve on this…

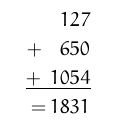

This is the sort of timing I remember for the various points in the ride; they maybe off by 10-15 minutes or so [except the start and end times].

0510 Ride Begins

0545 Petrol Pump

0610 Panvel Exit

0650 Khopoli Exit

0710 Lonavala Exit

0730 Kamshet

0800 Wakad

0825 Sam@IUCAA

So far so much for the ride now for the real work that had to be done. Which will take more of my time and energy and would be also less rewarding.

The RTO

Well my last visit to the Mumbai RTO for the learners license was not a particularly cheerful one. Last time I had visited the Pune RTO it was five years back in 2003, when I got the WindWolf transferred to my name.

Pathi had come to Samir’s at 9:30 we chatted for a few minute. We started for the Alandi Road [अाळंदी रोड] RTO office, where I had last time got the extension, at about 10ish. We met another traffic snarl at the Holkar bridge, just before the area of The Bombay Sappers. There is a ghat here, which is just one of the numerous buildings built by the one of the able and admirable lady rulers of India,

Ahilyabai Holkar [अहिल्याबाई होळकर] in the late 18th century.

Ughhh, so much I hate these jams …. People just won’t listen, there were two wheelers even on the side footpaths, trying to get an edge [of a few seconds] over the other riders [And then where are pedestrians supposed to go?]. All this for what, reaching their respective destinations just 2 minutes before?

I knew we had to take a left turn after the Holkar bridge. But thereafter I did not remember the way… So I did the best, when in doubt, ask! And that we did. So finally we reached the RTO office, when I saw it I remembered it.

As soon as you are near the gate there is a line of ‘agents’ greeted us, though not they were not these ones

here. But they all bore one similarity to the Agents of The Matrix, they all wore dark goggles. And no ordinary goggles were these; they were the ones not to be hidden. “Never Hide” says baseline of the latest ad campaign by Ray-Ban and believe me these people were following it religiously. And they

were definitely

not hiding. Maybe they will make a good footage for the next ad series. The goggles they wore were the same yet different, meaning they all had golden frames with dark glasses. No other type of Ray-Ban would suffice, it doesn’t fit

the requirements.

The trend of wearing starched cotton shirts [preferably white], with one or two thick gold chains hanging down the neck and sporting a Ray-Ban is a sort of status symbol in Western Maharashtra. Every Tom-Dick and Harry, who is a bit affluent will have one Ray-Ban. And those who do not have one, want one.

Anyways so all these agents ask is what work had to be done. Then I got one, and explained what exactly I wanted. So he agreed, and the cost was settled. I specifically told him that I wanted the papers today only, and that is why I am paying him his share. So then he told me the procedure. The procedure was very simple[?] and was as follows:

[FYI: There are two RTO offices in Pune city, one at Alandi Road, and another one near Sangam bridge [संगम पुल], the distance between them is about 8-9 kms. Its not that they are representing different regions, but they are part of the same office.]

Step 1: Fill a fee of Rs. 60. [This fee was told to me as Rs. 160, which I learnt later.]

But there is a catch here, as already told we were at the Alandi Road Office, this fee was to be deposited at the Sangam Bridge Office.

Step 2: Fill up a form for the re-registration, which has to have the details of the vehicle. This form should have the chassis and engine number which has to be embossed from the vehicle body. Any vehicle has the chassis and engine number imprinted on the body itself. This is sort of an unique ID that the vehicle has got.

With the form following documents were to be attached.

- The original RC book.

- Valid insurance papers.

- A PUC

I had all these so no need to worry.

Step 3: The RTO will then inspect the vehicle in terms of its condition, and the original papers along with their validity. Then the RTO will decide, whether to give the extension or not. Will stamp the RC book with his due sign.

This was it and we were done. 🙂

The Steps 2 and 3 were to be performed at the Alandi Road Office. Why this to and fro business between these two offices I do not understand [and I guess no body else does]!

So be it….

So the agent said that he will manage for paying the fees at the Sangam Bridge office, and also reassured that we wont have to do anything. Okay then he said he will be sending a person at the Sangam Bridge office and said that I give him the fees first, so I did. The time was about 10:30ish. We were told that by 12 we would be done with the work there. So by 12 it will be achieved what I had come to do. He said as soon as the person comes with the paid receipt from the Sangam Bridge office he will call me, till then i have to wait.

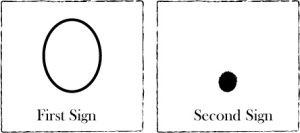

So me and Pathi went under a cozy shade of a tree nearby and waited. We were standing in front of a ground where there were two huge figures of “8” where the novice riders were going to give their tests for their driving licenses. Supposed

ly if you can drive the bike around the figure of “8” you are eligible for the license. Why this test is so or who devised this test is something lost in the mists of time or I do not know where to ask this question. Some of the more adventurous ones were actually practicing on the track.

Pathi had a lot of nostalgic memories of being here, some 10-12 years back. He narrated the incidents that took place at that time, when the people who actually had come to give the test fell on the “8” track. They say “driving is a privilege not a right.” And to get this privilege you have to give this test. Maybe this was true in the times of Nehru and pre-liberalization, but has not driving vehicles become a sort of necessity in this era. Given the pathetic and bad shape of the public transport, why won’t people choose to get their own vehicles to reach their destinations? If the authorities can provide cheap and reliable public transport why won’t people use it? Why do most of the people choose to buy their own vehicle, rather than use the public transport? I think one of the main reasons is the un-reliability of the public transport. This is true especially for the PMT buses in Pune. Mumbai has I guess the best public transport systems in India both on tracks and on road. Though I did find Delhi’s metro service very good, but the same cannot be said about the buses, autos and rickshaws there. They say Kolkata’s metro service is also good, but i haven’t been there and seeing is believing. And for Bangalore [from what I have witnessed and heard] the situation is as same [or worse] as Pune. I think both the cities are competing with each other as to how worse you can get in terms of roads and the traffic on them.

Most of the PMT buses are in really bad shape. They do not even look good even in the outer appearance, the engines are screaming to get in better shape and I think need an overhaul and servicing urgently. Ughhhh! Compared with the BEST buses PMT don’t stand any where near. Maybe they should learn a lesson or two from them. Some times the question comes to my why should be there so much difference between the buses. Is it due to the fact that most of BEST buses are Ashok Leyland make and most of the PMT buses are TATA make?

This is for the traffic on the road, but what about the roads themselves? In Pune the roads that I saw this time, were worse that I ever saw in the ten years. All the roads are “repaired” of potholes, but the repairing is done in “patches.” So that you have a small patch of even, repaired road and then some bad road and then the cycle repeats endlessly. This is more irritating than having a road full of potholes. The only roads which were free of potholes were those made of concrete. So is making all the roads of Pune concretized, the only concrete solution to the problem? Or can it be done by managing properly what we already have? Everybody who had to visit through the University circle maybe 2-3 years back will have vivid memories of the kind of nasty jams that were present during the construction of the now completed fly-overs. The entire University road from Shivaji Nagar was taken hostage for the construction of these fly-overs. The scheduled date was far from over, but the fly-overs were far from over at that time [if I remember it correctly the scheduled date of completion was somewhere in October-November 2005]. The amount of work hours and petrol lost in those jams was a terrible wastage of resources. Now that fly-overs are complete had everybody forgot the horror that they were subject to during those days? People who were responsible for this “delay” must be brought forward and held accountable for it. It must be people, it cannot be the concrete or the pillars that caused the delay. So who was responsible, were it the builders or the government bureaucracy or was it the “common man” who did not react to the atrocities committed?

So much for the road and the traffic now back to the RTO’s office in Alandi Road. It was already 11:30 and we were not called by the agent. So I went and enquired about it, he said that the person who had gone to the Sangam Bridge office had not come back. So we had to wait. Now the only worrying factor was that the original papers with him. Maybe it was nothing to worry for them but for me it was for I had no copies of the RC book or the insurance papers. Even if I had the copies original are original. As the time was passing and no information about the person at Sangam Bridge office I was getting impatient. I pinned the person many times about the same, but he assured me as soon as the person from the Sangam Bridge office would some my work would be done in 15 minutes.

The RTO’s office at Alandi Road is huge in terms of the extent, but it has no amenities whatsoever. I mean it has a few trees, placed randomly, but for what would be called as office, there are a few tin roofed sheds. This place was almost the same of what I had seen last time, five years back. So much could be done for this place, so many facilities could have made the place a better one for the people who do their jobs here, and also for those who come here to get the work done. There was no visible sign of any toilet. When I enquired about one, they told me to go to a place behind an abandoned room. But behind that room the space was entirely open. I just could not go there. Then at the other corner of the plot there was a huge arrow with some thing written on the wall in huge alphabets,

येथे लघवी करु नये

[Please do not pee here.]

And just besides that there was an arrow which said मुतारी [Urinal] and pointed towards a shabby looking shed in the corner. Well then this was it, it was the urinal of the office. I dared to go there and use it. And not at all to my surprise, the toilet was in bad shape. There was a clogging of the wastewater and the stench was unbearable. Why this should be so? Why can’t the people of India provided with decent toilets? This is the bane of India. Anywhere you go the toilets are usually in bad shape. If you think you have got the worse one, wait till you go to the next one, and you will have to redefine the definition of worse. And what about women? What about the torture they have to go through when they use the public toilets? The bad condition of toilets is not just the characteristics of the government offices, the schools, colleges, hotels, bus and railway stops are equally bad. And most of the people feel, bad but are [like me] oblivious when it comes to do something about it. Who is responsible for this? When we are paying taxes to the government is it too much to expect clean and hygienic toilets? I don’t know when the things are going to change….

At the Mumbai airport they charge you Rs. 2 for using the toilets. And the toilets are ordinary in construct and cleanliness. Why this should be so?

And as far as some eateries or canteens are concerned the Alandi Road offers just a few taparis [टपरी], giving you vada pavs and other things. But hygiene is a big question mark. With the space available there, a decent canteen can easily be constructed, if the authorities will.

Anyways, back to the work. So the guy who was supposed to come back from the Sangam Bridge office, did came at about 12:45. My worry was that the work should get over before the lunch. So that we can have our own lunch in peace. But destiny had other plans for us. After that the ritual of filling up the form, in which they put the chassis number by rubbing a pencil on the paper, while the paper is pressed on the numbers embossed on the body of vehicle. With all the details filled in we went to the office of the officer-in-charge, which was really a room with a shed and a few windows. The officer had an attendant who checked all the documents before passing on to the officer-in-charge. When the documents were presented the officer came and looked at the chassis number on the vehicle. And asked me

ईडिंकेटर वैगरे सुरु अाहे ना?

[Are indicators etc. working?]

When he was assured of that he just signed the documents and we were done. Only a stamp from some office was required, which would take 5 more minutes, I was told. So happy, I was. So after 5 minutes the actual sign and stamp happened and gave the remaining money. And then I was told something I was not at all prepared for. After the checkup here we were supposed to go back to the Sangam Bridge office and take the sign of another officer there, and get the work done registered in a register. What the Efff? [Mind you, Efff is a four letter word.] I meant this was not told to me originally, nor was part of the deal, I was not supposed to go to the Sangam Bridge office!!

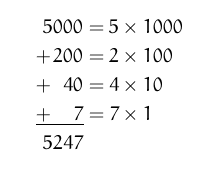

Anyways, he told me that at the Sangam Bridge office, the work is minimal and will be done very easily. It was a two step process. So add these two steps to the three I have already listed.

Step 4: Get the Officers sign on the papers.

Step 5: Get these papers to a clerk, who will do the actual re-registration in a register. The clerk will do the actual stamping on the RC book, of the extended date.

And after this we are really done.

Our agent said that after submission of the documents the clerk will tell us, after how many days we had to come back, to collect the documents. This news was not certainly good. I had to get the documents today. So I asked him, are there any other agents, who can help me there. He gave me number of some other guy there, who sits under Tree No. 4 [झाड क्रमांक ४] at the Sangam Bridge office. Curiously when we went there I saw that the trees are labelled by the numbers and the agents actually sit under them.

We were feeling quite hungry, so decided to have lunch first and then go for the remaining work.

पहिले पेट पुजा, फिर काम दुजा.

So we went to Bamboo House in Shivaji Nagar and finished lunch by 2:15 and by 2:25 we were at the Sangam Bridge office. We had called the agent at the Sangam Bridge office saying that we, were coming there and that he should help us. When we went under Tree No. 4 the person we were looking for was not there, he had gone for lunch. We were told by the others agents that this was a work which was easily doable by us, and we should go to the third floor to get it done. So we did. We went to the third floor and in the corner was office of the officer concerned. Here again there was an assistant/clerk who checked the documents before sending it to the officer-in-charge. He checked and promptly sent it in. But after 15 minutes of wait there was no response. And at 1440 hrs the officer-in-charge went for lunch. Well, we wait. Then there came peon, who cleaned the office. So I enquired with him about the process that has to be done, he explained in details.

Officer in charge came back at about 1520 hrs, all other people were going into his cabin for getting the documents signed. After the peon prompted I also went in. The officer-in-charge was already busy signing the heap of documents that was unleashed before him. I told him what my purpose was, and that I had already given the documents in. So he said in a very assuring tone:

तुम्ही दिले अाहे ना, मग होऊन जाईल.

[You have submitted [the documents], then it will be done.]

And done it was, in next five minutes the documents came to the clerk who was sitting outside the cabin. Then he told us that we had to go to the ground floor, for actually getting the registration done. And so we descended, to the lower floors. The life here was bustling with activity, people running around seemingly randomly. The system here is something like this. Every clerk has been alloted a few ‘series’ of the registration numbers. By this it is meant that each clerk only does work for a certain number, like lets say MH-12 AG or MJE etc. So first we had to find the clerk who has our series. In the lists that were present, my series MGE did not show up anywhere. I became a bit tense, everybody thought it was MJE and general confusion followed. Everywhere, everyone was busy. Then finally I was directed to one person, who seemed to be the master in all such matters. The situation became further tense for me, when someone told that this registration was at Nigdi [निगडी] RTO’s Office. Then someone saw the RC Book and to my reassurance told that, although the passing is from Nigdi office, it had been transferred to Pune Office.

The know-it-all guy directed me to, one person, who was in all this chaos not looking busy at all. When I presented him with the papers, he told me that this was not his series to work with and asked me to go back to the know-it-all guy. Then I clarified to him that, ‘that’ guy only had send us to him and further added the newly acquired information about the transfer from Nigdi RTO. Then he looked at the watch it was 1530 hrs and told us to come back at 1700 hrs. I asked his whether the work would be done or not, he replied it would be definitely done.

So we had to wait till 1700 hrs. But at that time, I thought about the agent we had left under, Tree No. 4. I called him and asked him whether anything could be done. He did not reply positively. So I went and met him under the Tree No. 4. He was a bit pissed off that we did not come to him first, and was totally non-cooperative. He told that once we go directly to the clerks/officers there is no deal for them left. And was visibly annoyed, he also called the agent at Alandi Road office and told that we had done this. So anyways I asked him would he be of any help now, he said no, and we left him.

Now back in the office we had no other option but to wait. So we waited in the great hall on the ground floor, where all the counters for various activities were present. There were counters for licences, fees, registration etc. Also on the boards various rules and by rules were present, along with portraits of national heroes. The posters gave in written and details how complicated it was to get the work done, it actually told how many times one had to go to and fro even between the two offices, to get even simple work done. So be it. Also the various district wise numbers of the vehicles for Maharashtra state were given.

After watching all this we felt a little bored it was 1600 hrs already. Pathi suggested that I go and check on the progress of the work. Main worry was the fact that we did not have any proof that we had submitted the documents to them, all the papers and receipts were attached with the form, so if the form is lost or misplaced I will be left with nothing. And the sort of chaos that was present there it was very likely that it will get lost. So I went to check. The clerk did have a good memory, for he recognised me immediately, and also reminded me that he had asked me to come at 1700 hrs. He sort of warned me that, why he should not ask me to come next day for collecting the documents? With this sort of warning I receded back to our hall where we sat from last few minutes.

Just at the entrance to RTO’s office there is a cabin of the PRO. This cabin has a seat for the PRO and a CGI [computer graphical interface] which had the links to all the services that one could avail from this office. This console was touch sensitive and was courtesy of some IT company. So we went and checked with some details, they were explicit and well done. But you had to come here to access this, why cannot they put this on the internet? It would be great help if they do. Here in the great hall I noticed another thing, there were paan [पान] and gutkha [गुटखा] spits on all the pillars, corners and walls inside the hall. This is another major thing that annoys me, people spitting where ever they find space. The problem is acute in the stairways, where the corners are especially targeted for this purpose. People don’t feel ashamed for this and they do it with pride. When will this attitude change? It they fined Rs. 500 per spit. I think some things will change…

So it was about 1650 hrs, the time that I was given was coming nearby. So I went to him and to my relief my they had found the records for series MGE and also located entry of my vehicle in that register. And after I had gone, they did the needful and entered the renewed registration in the register. Finally it was done, or so I thought.

The clerk who showed me the entries, told me that I have to submit xerox [carbon?] copies of the insurance and the RC book. Now after all this only these copies were not going to stop me. So I just dashed to get them, when he called me back again and told me that it was not needed, as he had checked the originals….

Phewwww…..

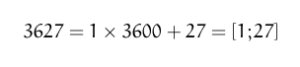

So finally the day came to a close at 1705 hrs. And below is the result of a complete days work.

The Doom Day Now Reset to 15/5/2013

I felt like resetting a nuclear device, to five years later, when this ordeal has to be repeated again. Till then

I ride,

The WindWolf with pride…