As a technology, elevators were mandatory for having high rise apartments. You really don’t want to climb up 35 flights of stairs to just get home. My experience with elevators (or lifts as they are more commonly called in India) has been rather strange at times and continues to be so. And I am pretty sure, this is something most people also experience. If you look at it with scrutiny, it is not a strange experience per se, but I found it fascinating nonetheless. As the title of the post suggests, it is about how we perceive the passage of time when we are in an elevator. Now, typically, they would take less than a minute, sometimes perhaps 10-20 seconds to traverse the required distance. Now, here I am considering typical apartment buildings which I have lived in. Not the skyscrapers with 100s of floors. The lift takes about 12 seconds, as timed using a stopwatch to reach my floor if there are no other stops. Of course, if there are stops on intervening floors when people get in or get out, this is longer. So this is the minimum possible time for the lift to take this floor, both ways. That is from my floor to the ground floor and from the ground floor to my floor.

The distance between the ground floor and my floor is constant. The lift and its motor produce the same acceleration and hence same terminal velocity, and the time taken is the same (as measured with a chronometer). I used a quantum-temporal-displacement-chronometer to be sure about time measurement. So our experience of this short travel should also be the same. But this is far from the case. Traveling in the lift gives a variety of experiences. But most strongly it affects how we perceive the passage of time during this short journey. Sometimes it is as if the ground floor is touched as soon as you press the 0 button on the control panel, while at other times it seems time itself has slowed down and it is taking centuries to cover that trivial distance. You may look at the panel displaying the current floor several times during these few seconds and yet it somehow feels lift is moving too slowly. And at times when you are not looking at the panel, and are lost in your thoughts, it chimes to indicate the ground floor has arrived. And you are surprised that it took such a short time. So what kind of blackmagicfuckery is this you wonder? That we subjectively experience something entirely different in terms of time perception is nothing new, but in the case of an elevator, it is so much striking and a part of everyday experience.

I have concocted explanations for the two cases one in which we deem the lift going too slowly and one in which we perceive it be too fast. In the first case, when we perceive the lift to be too slow, we are perhaps not thinking about anything else. Our entire cognitive apparatus and sense organs (eyes and ears) are solely focussed on getting to the destination. Hence, we tend to only look at the floors numbers on the display panel again and again. Expecting it to change often, and our expectation time, the way our neurons are firing is much faster than the real-time. The anticipation is that it should go faster whereas it is going at its own pre-determined pace. Hence, there is a cognitive dissonance that we experience as lift going too slowly. This is even more pronounced if we are in a hurry to get somewhere or are already late. I have seen people press the buttons on the control panel again and again in the hope that it will get them there faster, but it doesn’t work that way. Objectively measured the lift will take the pre-determined time to reach its destination. You are only subjectively experiencing that it is taking longer. Perhaps two persons in the same lift will have a completely different perception of time depending upon their mental states.

Now coming to the other case, in which we experience the time to be too short, perhaps our cognitive system is already too loaded. This is when before entering the lift we are deep in a thought chain that we are processing. In such a scenario, we expect the lift to just take us to the destination once we press the button. Our schema for the elevator is activated, we don’t have to do any cognitive processing once we press the button. The schema, as an automated response shaped by our experiences with elevators and induction, works seamlessly when not interfered with, assuming that the elevator is behaving in its normal manner. I have had experience of an elevator which could close the door as you were trying to enter. It was almost as if the elevator waited like a predator to catch its pray. Some logic circuits in this elevator were fried, and it won’t let you off you when it caught your leg. Or the elevator might itself have a severe case of fear of heights (vertigo?), as told in HHGTG and would not want to travel to heights. But these being extreme cases, most elevators are domesticated and docile, doing the deed they are designed to do depositing and delivering cargo to destinations, despite the draconian ways in which some travellers might treat them.

Coming back to the explanation for the former case, perhaps due to no cognitive load we are trying to screw with the automated schema. We are just running the simulation of the schema for elevators in our minds, and confusing it with the real world out there. Hence there is a cognitive dissonance. We are expecting something in the mind, while we are seeing something in reality. I have also tried this experiment sometimes when this happens. I close my eyes and mentally calculate the amount of time that might have passed and try to predict the floor that I might have reached. I open my eyes to check if I have guessed correctly but most of the times I am incorrect in the guess.

When we have company in the lift, the temporal experience can be altered and can be subjective as well. If you are with a person whom you find attractive or admire, you might feel that the time taken was perhaps too short. On the other hand, if it is somebody whom you find disgusting or un-attractive, the same journey might seem like a lifetime or a life sentence. In this case, perhaps the cognitive system has become completely Epicurean (when it is not?) in its approach and wants to maximise the good times and minimise the not-so-good ones.

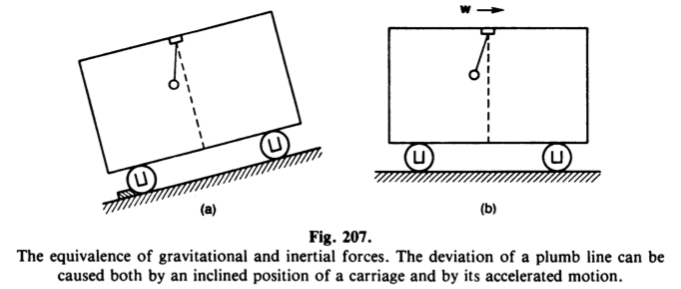

But this does not end the discussion of the elevators. Experiments in elevators provide some useful insights in fundamental physics. This is related to the concepts of frames of reference and the so-called equivalence principle. Elevators are used in Gedanken experiments for thinking about the equivalence principle, which later gave rise to the general theory of relativity.

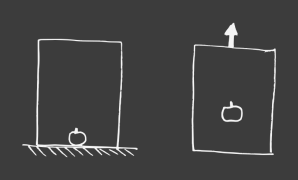

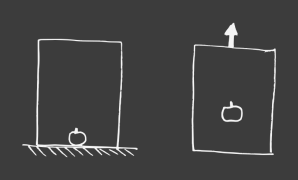

Apple falling inside a box that rests on the Earth. Indistinguishable motion when the appl is inside an accelerated box in outer space.

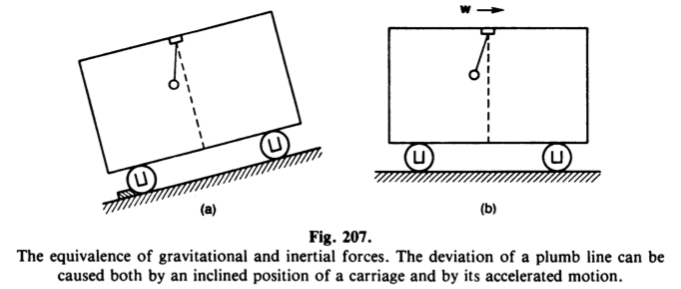

The equivalence principle states that to an observer in a freely falling elevator the laws of physics are the same as in the inertial frames of special relativity (at least in the immediate neighbourhood of the centre of the elevator). The effects due to the accelerated motion and to the gravitational forces exactly cancel. An observer sitting in an enclosed elevator cannot, if he observes apparent gravitational forces, tell what portion of these correspond to acceleration and what portion to actual gravitational forces. He will detect no forces at all unless other forces (i.e., other than gravitational forces) act on the elevator. In particular, the postulated principle of equivalence requires that the ratio of the inertial and gravitational masses be M_i/M_g = 1. The “weightlessness” of a man in orbit in a satellite is a consequence of the equivalence principle. Pursuit of the mathematical consequences of the principle of equivalence leads to the general theory of relativity.. –

From Kittel Mechanics – Berkeley Physics Course Volume 1

Another fundamental aspect of physics which uses elevators is the notion of inertial and non-inertial frames of reference. An inertial frame of reference is one in which the particle experiences no acceleration (either transitional or rotational).

Our ability to say whether or not a particular reference frame is an inertial frame will depend in a strict sense upon the precision with which we can detect the effects of a small acceleration of the frame. In a practical sense, a reference frame in which no acceleration is observed for a particle believed to be free of any force and constraint is taken to be an inertial frame.

Now an elevator moving with a constant downward acceleration will be no different than the gravity that we experience on the surface of the Earth. No dynamical experiments conducted inside the elevator will ever tell us whether the elevator is moving with constant acceleration or it is stationary at the surface of the Earth. To know what is the actual case we have to go and perform experiments / take observations outside the lift.

Thus the humble lift or elevator has more to offer to you than just taking you from point A to point B in your daily routine.