What could be more “organic” and “natural” than looking at a pristine forest with a variety of tree forms and leaf forms of various shapes and shades, with inflorescences of variety of shapes, sizes and colours? Mathematicians and physicists are often accused of being not able to enjoy nature and because mathematics and physical theory is so “abstract” and nature is so “organic”. Organic growth is in the form of variety of morphologies of roots, branches, flowers shapes and arrangement, leaf shapes and arrangements, while mathematics typically is abstract graphs, equations, symbols and numbers. How can these two possibly have anything in common? This has also to do with how biology is traditionally taught. While physics has mathematics at its foundation, the teaching of biology doesn’t acknowledge any need for mathematics – it is mostly descriptive as it was in its early stages a couple of centuries later. This is more so at the school level teaching of biology. So this creates an impression in the students and teachers alike that mathematics is not a part of “biological” nature and it is only reserved for falling bodies and ascending projectiles.

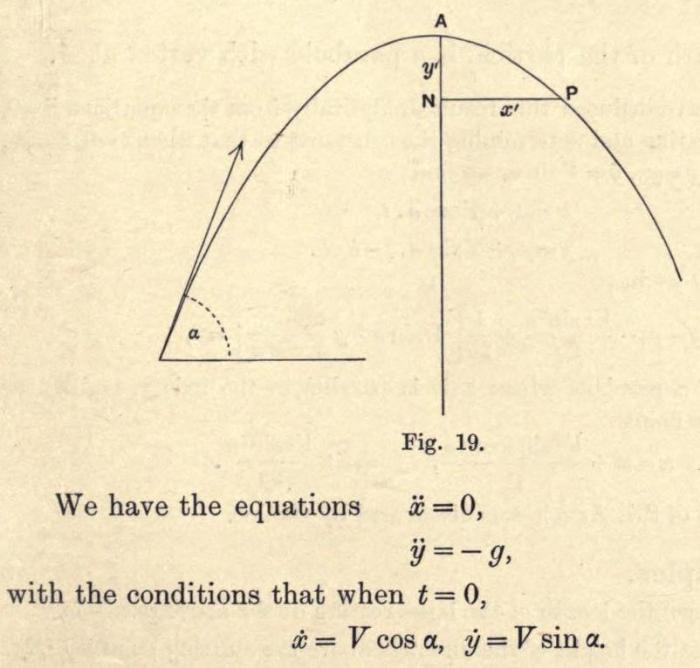

What can be similarities in the two images? One is abstracted representation of motion of a body in algebraic and graphical format and other is organic growth of a plant showing its branching and similar leaves with its pigmentation of chlorophyll.

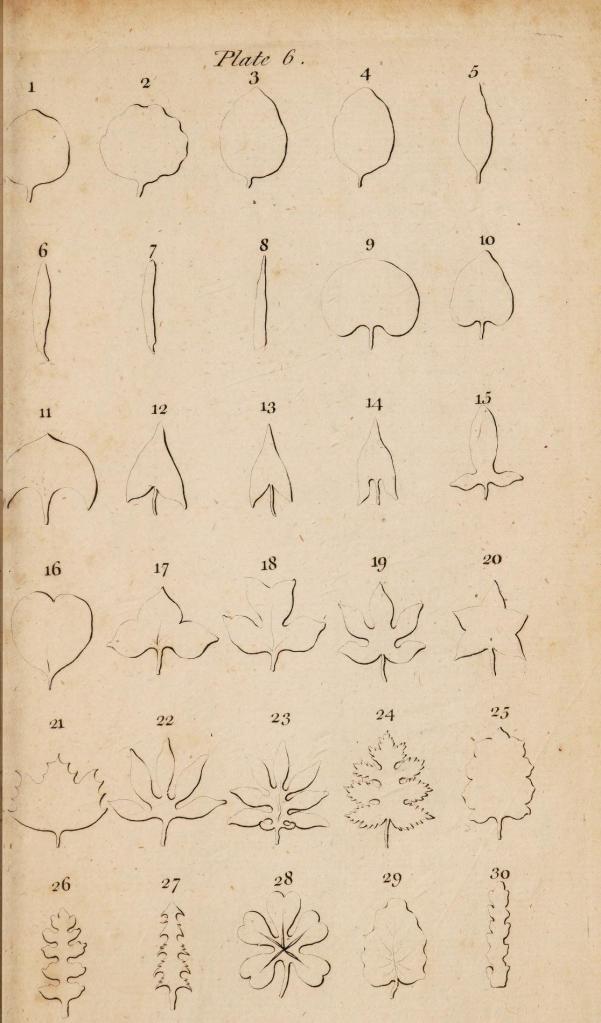

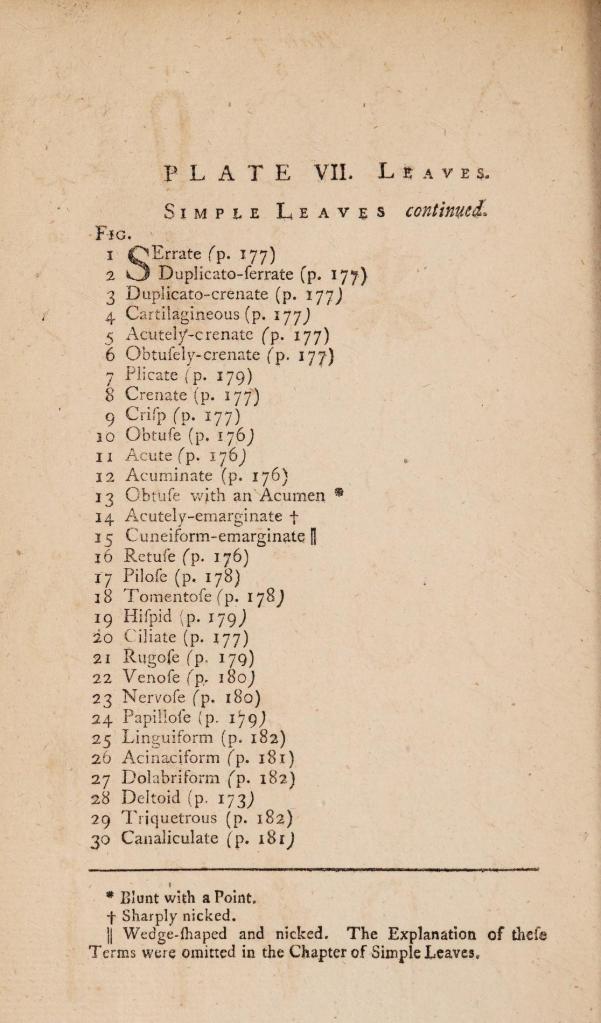

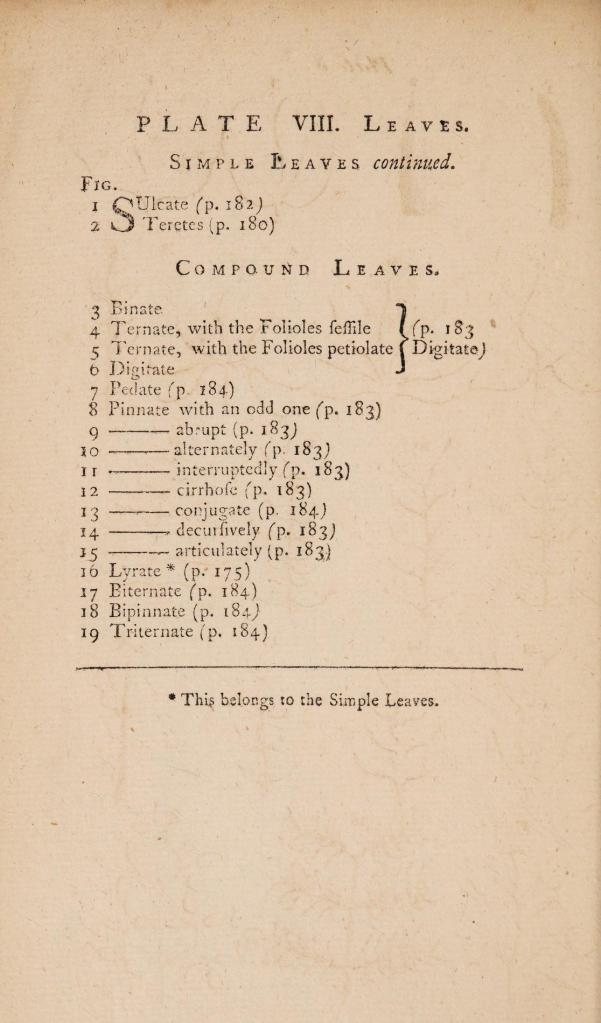

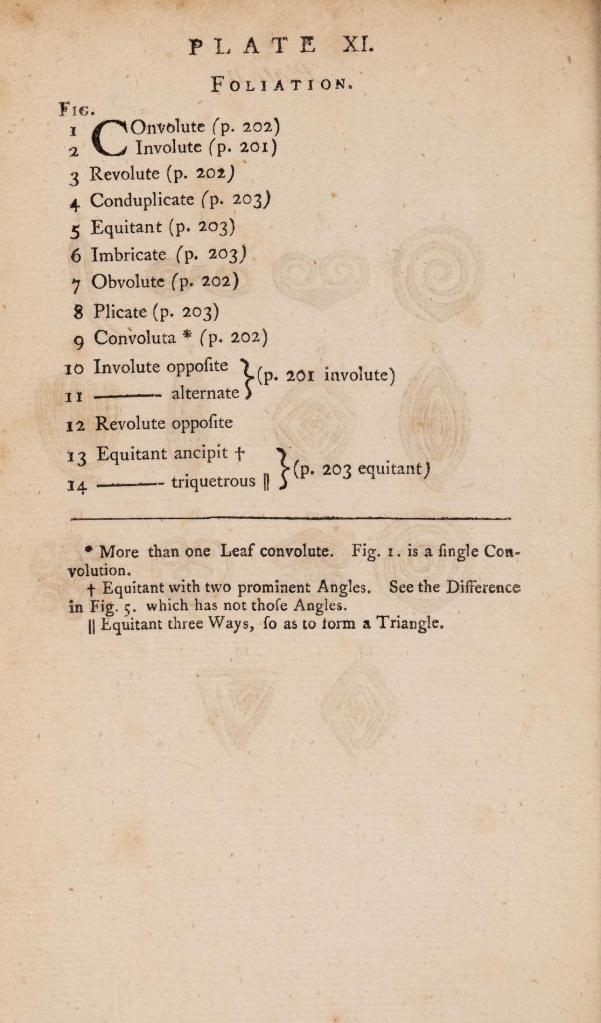

Of course the variety of forms and their classification is one of the foundations of biology. Linnaeus used the morphological differences and similarities to form his classification system.

Linnaean system brought order to seemingly diverse and chaotic forms of natural world. Linnaeus named the different forms. Naming is the first step in studying anything. Naming helps in categorisation, which is one of ways to formation of concepts. This led to further finer classification of the system as whole which now includes both flora and fauna. Then began the programme of finding organisms and classifying them in existing categories with descriptions – or creating new ones when the existing ones did not fit – became the normal way of doing biology in the nineteenth century. Even now finding a new plant or animal species is treated with celebrated as a new discovery.

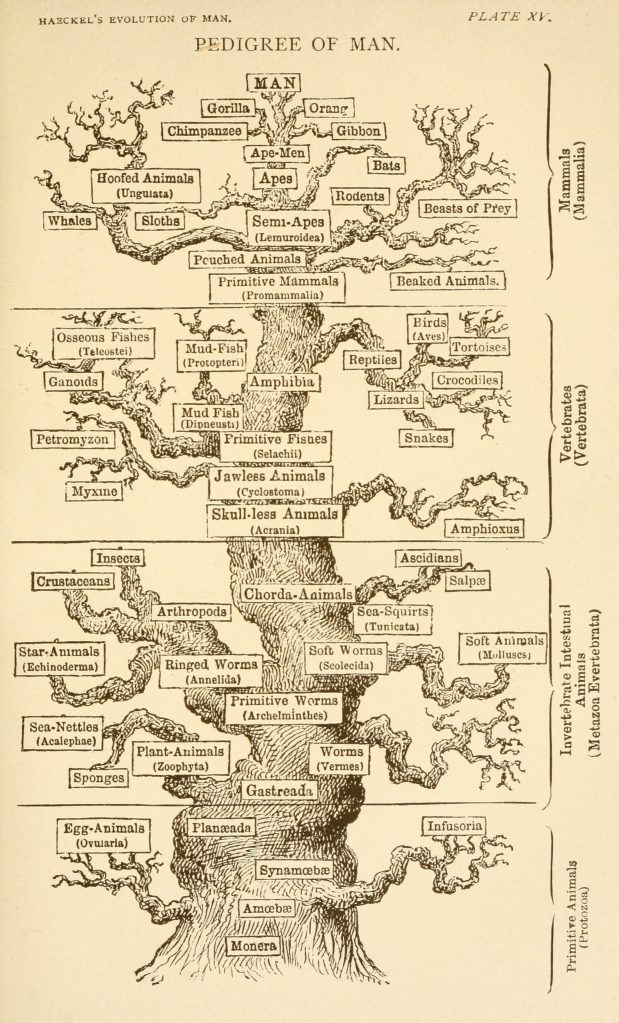

Darwin in his thesis about evolution by natural selection used the differences and similarities of the form as one of evidence. He theorised that organisms that have evolved from common ancestors will show similar forms with slight variations. Over long periods of time these slight variations evolve into larger variations which ultimately leads to a completely different species. Fossil records tell us about ancestors and current relatives of organisms.

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved. (emphasis added)

The morphologies tell us about related species, the ancestries and divergences from there. The fossils tell us the ancestors, the missing links. So finding organisms, both extant and extinct, to fit in the jigsaw puzzle of tree of life became the standard programme in biology. This enabled us to construct the tree of life. Ernst Haeckel’s version of the tree, depicted below, is highly anthropocentric which places humans at the apex of evolution. This is rather common misconception about evolution – humans are not at apex of evolution or the prime product of it as some would have us believe – we have co-evolved with all the current extant species. Evolution by natural selection is not anthropocentric, it is indifferent to humans and other organisms alike. Daniel Dennett likens it to universal acid, and makes a point that it is not only applicable to living systems, but applies to any system which fulfil the three required criteria.

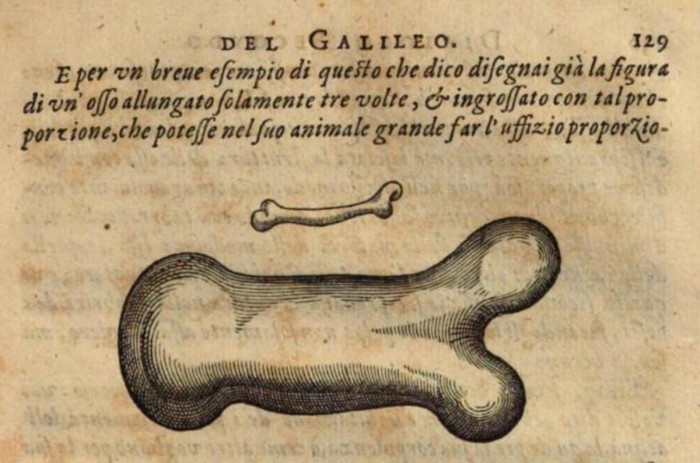

But can we make sense of similarities of the form in terms of mathematics? Can we find mathematical algorithms which will generate forms, as they generate trajectories of moving projectiles? Looking at similarities in form, it is Galileo who was one of the first to discuss the problem of scaling and its effect on form.

To illustrate briefly, I have sketched a bone whose natural length has been increased three times and whose thickness has been multiplied until, for a correspondingly large animals, it would perform the same function which the small bone performs for its small animal, From the figures here shown you can see how the proportion of the enlarged bone appears.

…

Whereas, if the size of a body be diminished, the strength of that body id not diminished in the same proportion; indeed the smaller the body the greater its relative strength. Thus a small dog could probably carry on his back two or three dogs of his own size; but I believe that a horse could not carry even one of his own size.

At the start of twentieth century we had a few classics which gave a strong mathematical flavour to the study of the biological forms and scaling – The Curves of Life by Theodore Cook (1914), D’arcy Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1917) and Julian Huxley’s Problems of Relative Growth (1932).

The kind of mathematical treatment that entered in study of biology by above classics looked at the mathematical aspects of morphological forms in organisms. The Curves of Life looks at the spiral forms which are found in nature, and also in various human creations – architecture and art.

Despite tremendous success of Darwin’s theory, physics and mathematics were in a separate compartment from biology. There seemed to be no common elements, while biology became more and more descriptive with focus on the form, but not mathematical.

The word “form” in this article will refer to the shapes of material objects, the arrangement in space of groups of them, and the arrangement in space of their component parts. Our appreciation of form is partly sensory, but we can be helped by measurement and calculation to gain some confidence that what we perceive is not entirely unconnected with the outside world. (Physical Principles underlying Inorganic Form – S.P.F. Humphreys-Owen)

But this is a folly. Nature and organic growth is as mathematical as is the description of a projectile flying under gravity. Perhaps the mathematical description is

In my experience a lot of young children who take to biology do so because they hate mathematics or computations. In India there are even streams at +2 level which allow you to shun mathematics for biological subjects. This utter hatred for mathematics is, IMHO, due to a carelessly designed and too abstracted mathematics curriculum at the school level – a curriculum which takes out the soul of mathematics and puts on a garish display of the cadaver of mathematics with bells and whistles. But this post is not about the problems of mathematics education, I have talked about it elsewhere.

The aim of this series of posts is to touch upon the inherent mathematics and algorithms in the natural world. How nature is mathematical especially in living and non-living things. How can algorithms generate natural forms? In the next posts in this series we will explore how the ideas of mathematical models can explain the variety of forms that result from natural selection in environment and possibly why only those forms can be found.

Note: All photographs were taken by me over the years. Only now I am able to piece a narrative linking them together.