It is difficult now to challenge the school as a system because we are

so used to it. Our industrial categories tend to define results as

products of specialized institutions and instruments, Armies produce

defence for countries. Churches procure salvation in an

afterlife. Binet defined intelligence as that which his tests

test. Why not, then, conceive of education as the product of schools?

Once this tag has been accepted, unschooled education gives the

impression of something spurious, illegitimate and certainly

unaccredited.

– Ivan Illich (Celebration of Awareness)

education

Einstein on his school experience

One had to cram all this stuff into one’s mind, whether one liked it or not. This coercion had such a deterring effect that, after I had passed the final examination, I found the consideration of any scientific problems distasteful to me for an entire year … is in fact nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry; for this delicate little plant, aside from stimulation, stands mainly in need of freedom; without this it goes to wreck and ruin without fail. It is a very grave mistake to think that the enjoyment of seeing and searching can be promoted by means of coercion and a sense of duty. To the contrary, I believe that it would be possible to rob even a healthy beast of prey of its voraciousness, if it were possible, with the aid of a whip, to force the beast to devour continuously, even when not hungry – especially if the food, handed out under such coercion, were to be selected accordingly.

Seeing that even almost a hundred years later it is almost unchanged gives one an idea of how little effort has gone into changing how we learn.

On respect in the classroom

If you are a teacher (of any sort) and teach young people, don’t be disheartened if the students in your class don’t respect you or listen to you or maintain discipline. Even great philosophers like Socrates and Aristotle has a tough time dealing with their students

Socrates grumbled that he don’t get no respect: his pupils “fail to rise when their elders enter the room. They chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, and tyrannize over their teachers.” Aristotle was similarly pissed off by his students’ attitude: “They regard themselves as omniscient and are positive in their assertions; this is, in fact, the reason for their carrying everything too far.”Their jokes left the philosopher unamused: “They are fond of laughter and consequently facetious, facetiousness being disciplined insolence.”

– Judith Harris The Nurture Assumption

That being said, the students are also very perceptive about the knowledge of the teachers, and know who is trying to be a cosmetic intellectual.

Cosmetic Intellectuals (+ IYI)

In the last few years, the very connotation of the term intellectual has seen a downward slope. Such are the times that we are living in that calling someone an “intellectual” has become more like an insult rather than a compliment: it means an idiot who doesn’t understand or see things clearly. Now as the title of the post suggests it is this meaning, not the other meaning intellectuals who know about cosmetics. Almost two decades back Alan Sokal wrote a book titled Intellectual Impostures, which described quite a few of them. In this book, Sokal exposed the posturing done by people of certain academic disciplines who were attacking science from a radical postmodernist perspective. What Sokal showed convincingly through his famous hoax, is that many of these disciplines are peddling out bullshit with no control over the meaning contained. Only the form was important not the meaning. And in the book, he takes it a step forward, showing that this was not an isolated case. He exposes the misuse of the technical terms (which often have precise and operational meanings) as loose metaphors or even worse completely neglecting the accepted meaning of those terms. The examples given are typical, and you cannot make sense of what is being written. You can read, but cannot understand. It makes no sensible meaning. At this point, you start to doubt your own intelligence and intellectual competence, perhaps you have not read enough to understand this complex piece of knowledge. It was after all written by an intellectual. Perhaps you are not aware of the meaning of the jargon or their context, hence you are not able to understand it. After all there are university departments and journals dedicated to such topics. Does it not legitimise such disciplines as academic and its proponents/followers as intellectuals? Sokal answered it empirically by testing if presented with nonsense whether it makes any difference to the discipline. You are not able to make sense of these texts because they are indeed nonsensical. To expect any semblance of logic and rationality in them is to expect too much.

Nassim Taleb has devised the term Intellectual Yet Idiots (the IYI in the title) in his Incerto series. He minces no words and takes no bullshit. Sokal appears very charitable in comparison. Taleb sets the bar even higher. Sokal made a point to attack mostly the postmodernists, but Taleb bells the cats who by some are even considered proper academics, for example, Richard Dawkins and Steven Pinker. He considers entire disciplines as shams, which are otherwise considered academic, like economics, but has equal if not more disdain to several others also, for example, psychology and gender studies. Taleb has at times extreme views on several issues and he is not afraid to speak of his mind on matters that matter to him. His writings are arrogant, but his content is rigorous and mathematically sound.

they aren’t intelligent enough to define intelligence, hence fall into circularities—their main skill is a capacity to pass exams written by people like them, or to write papers read by people like them.

cosmetic

- relating to treatment intended to restore or improve a person’s appearance

- affecting only the appearance of something rather than its substance

It is the second sense that I mean in this post. It is rather the substance of these individuals that is only present in the appearance. And as we know appearance can be deceiving. Cosints appear intellectuals, but only in appearance, hence the term cosmetic. So how does one become a Cosint? Here is a non-exhaustive list that can be an indicator (learn here is not used in the deeper sense of the word, but more like as in rote-learn):

- Learn the buzzwords: Basically they rote learn the buzzwords or the jargon of the field that they are in. One doesn’t need to understand the deeper significance or meaning of such words, in many cases just knowing the words works. In the case of education, some of these are (non-comprehensive): constructivism, teaching-learning process, milieu, constructivist approaches, behaviorism, classroom setting, 21st-century skills, discovery method, inquiry method, student-centered, blended learning, assessments, holistic, organic, ethnography, pedagogy, curriculum, TLMs. ZPD, TPD, NCF, RTE, (the more complicated the acronyms, the better). More complicated it sounds the better. They learn by association that certain buzzwords have a positive value (for example, constructivism) and other a negative one (for example, behaviorism) in the social spaces where they usually operate in, for example, in education departments of universities and colleges. Not that the Cosints are aware of the deeper meaning of there concepts, still they make a point of using them whenever possible. They make a buzz using the buzzwords. If you ask them about Piaget, they know the very rudimentary stuff, anything deeper and they are like rabbits in front of flashlight. They may talk about p-values, 𝛘2 tests, 98.5 % statistical significances, but when asked will not be able to distinguish between dependent and independent variables.

- Learn the people: The CosInts are also aware of the names of the people in their trade. And they associate the name to a concept or of a classic work. They are good associating. For example, (bad) behaviorism with Burrhus F. Skinner or Watson, hence Skinner bad. Or Jean Piaget with constructivism and stages (good). Vygotsky: social constructivism, ZPD. Or John Dewey and his work. So they have a list of people and concepts. Gandhi: Nayi Taleem. Macauley: brought the English academic slavery on India (bad).

- Learn the classics: They will know by heart all the titles of the relevant classics and some modern ones (you have to appear well-read after all). Here just remembering the names is enough. No one is going to ask you what was said in section 1.2 of Kothari Commission. Similarly, they will rote learn the names of all the books that you are supposed to have read, better still carry a copy of these books and show off in a class. Rote learn a few sentences, and spew it out like a magic trick in front of awestruck students. Items #1 through #3 don’t work very well when they have real intellectual in front of them. A person with a good understanding of basics will immediately discover the fishiness of the facade they put up. But that doesn’t matter most of the time, as we see in the next point.

- Know the (local) powerful and the famous: This is an absolute must to thrive with these limitations. Elaborated earlier.

- Learn the language aka Appear academic (literally not metaphorically): There is a stereotype of academic individuals. They will dress in a particular manner (FabIndia?, pyor cotton wonly, put a big Bindi, wear a Bongali kurta etc, carry ethnic items, conference bags (especially the international ones), even conference stationery), carry themselves in a particular manner, talk in a particular manner (academese). This is also true of wannabe CosInt who are still students, they learn to imitate as soon as they enter The Matrix. Somehow they will find ways of using names and concepts from #1 #2 #3 in their talk, even if they are not needed. Show off in front of the students, especially in front of the students. With little practice one can make an entire classroom full of students believe that you are indeed learned, very learned. Any untoward questions should be shooed off, or given so tangential an answer that students are more confused than they were earlier.

- Attend conferences, seminars and lectures: The primary purpose is network building and making sure that others register you as an academic. Also, make sure that you ask a question or better make a tangential comment after the seminar so that everyone notices you. Ask the question for the sake of asking the question (

evenespecially if you don’t have any real questions). Sometimes the questions devolve into verbal diarrhea and don’t remain questions and don’t also have any meaning that can be derived from them (I don’t have a proper word to describe this state of affairs, but it is like those things which you know when you see it). But you have to open your mouth at these events, especially when you have nothing substantial/meaningful to say. This is how you get recognition. Over a decade of attending various conferences on education in India, I have come to realise that it is akin to a cartel. You go to any conference, you will see a fixed set of people who are common to these conferences. Many of these participants are the cosints (both the established and the wannabes). After spending some time in the system they become organisers of such conferences, seminars and lectures definitely get other CosInts to these conferences. These are physical citation rings, I call you to my conference you call me to yours. Year after year, I see the same patterns, so much so I can predict, like while watching a badly written and cliche movie, what is going to happen when they are around. That person has to ask a question and must use a particular buzzword. (I myself don’t ask or comment, unless I think I have something substantial to add. Perhaps they think in same manner, just that their definition of substantial is different than mine.) Also, see #5, use the terms in #1, #2 and #3. Make sure to make a personal connection with all the powerful and famous you find there, also see #4. - Pedigree matters: Over the years, I have seen the same type of cosints coming from particular institutions. Just like you can predict certain traits of a dog when you know its breed, similarly one can predict certain traits of individuals coming from certain institutions. Almost without exception, one can do this, but certain institutions have a greater frequency of cosints. Perhaps because the teachers who are in those places are themselves IYI+cosints. Teaching strictly from a prescribed curriculum and rote-learning the jargon: most students just repeat what they see and the cycle continues. Sometimes I think these are the very institutions that are responsible for the sorry state of affairs in the country. They are filled to the brim with IYIs, who do not have any skin in the game and hence it doesn’t matter what they do. Also, being stamped as a product of certain institution gives you some credibility automatically, “She must be talking some sense, after all he is from DU/IIT/IIM/JNU/”

- Quantity not quality: Most of us are not going to create work which will be recognised the world over (Claude Shannon published very infrequently, but when he did it changed the world). Yet were are in publish or perish world. CosInts know this, so they publish a lot. It doesn’t matter what is the quality is (also #4 and #5 help a lot). They truly are environmentalists. They will recycle/reuse the same material with slight changes for different papers and conferences, and surprisingly they also get it there (also #4 and #5 help a lot). So, at times, you will find a publication list which even a toilet paper roll may not be able to contain. Pages after pages of publications! Taleb’s thoughts regarding this are somewhat reassuring, so is the Sokal’s hoax, that just when someone has publications (a lot of them) it is not automatic that they are meaningful.

- Empathisers and hypocrites: Cosints are excellent pseudo-emphatisers. They will find something to emphathise with. Maybe a class of people, a class of gender (dog only knows how many). Top of the list are marginalised,

poorlow socio-economic status, underprivileged, rural schools, government students, school teachers, etc. You get the picture. They will use the buzz words in the context of these entities they emphathise with. Perhaps, once in their lifetimes, they might have visited those whom they want to give their empathy, but otherwise, it is just an abstract entity/concept.(I somehow can’t shake image of Arshad Warsi in MunnaBhai MBBS “Poor hungry people” while writing about this.) It is easier to work with abstract entities than with real ones, you don’t have to get your hands (or other body parts) dirty. The abstract teacher will do this, will behave in this way: they will write a 2000 word assignment on a terse subject. This is all good when designing things because abstract concepts don’t react in unwanted ways. But when things don’t go as planned in real world, teachers don’t react at all! The blame is on everyone else except the cosints. Perhaps they are too dumb to understand that it is they are at fault. Also, since they don’t have skin in the game, they will tell and advise whatever they have heard or think to be good, when it is implemented on others. For example, if you talk to people especially from villages, they will want to learn English as it is seen as the language which will give them upward mobility. But cosints, typically in IYI style, some researchers found that it is indeed the mother tongue which is better for students to learn, it should be implemented everywhere. The desires and hopes of those who will be learning be damned, they are too “uneducated” to understand what they need. It is the tyranny of fake experts at work here.He thinks people should act according to their best interests and he knows their interests… When plebeians do something that makes sense to themselves, but not to him, the IYI uses the term “uneducated.” (SITG Taleb)

Now one would naturally want to know under what conditions that research was done? was there any ideological bias of the researchers? whether it is applicable in as diverse a country as India? What do we do of local “dialects”? But they don’t do any of this. Instead, they will attack anyone who raises these doubts, especially in #6. They want to work only with the government schools: poor kids, poor teachers no infrastructure. But ask them where their own children study: they do in private schools! But their medium must be their mother tongue right? No way, it is completely English medium, they even learn Hindi in English. But at least the state board? No CBSE, or still better ICSE. Thus we see the hypocrisy of the cosint, when they have the skin in the game. But do they see it themselves? Perhaps not, hence they don’t feel any conflict in what they do.

So we see that IYI /cosint are not what they seem or consider themselves. Over the last decade or so, with the rise of the right across the world is indicating to everyone that something is wrong when cosints tell us what to do. The tyranny of pseudo-experts has to go. But why it has come to that the “intellectuals” who are supposed to be the cream of the human civilisation, the thinkers, the ideators, so why the downfall? Let us first look at the meaning of the term, so as to be not wrong about that:

The intellectual person is one who applies critical thinking and reason in either a professional or a personal capacity, and so has authority in the public sphere of their society; the term intellectual identifies three types of person, one who:

- is erudite, and develops abstract ideas and theories;

- a professional who produces cultural capital, as in philosophy, literary criticism, sociology, law, medicine, science; and

- an artist who writes, composes, paints and so on.

Intellectual (emphasis mine)

Now, see in the light of the above definition, it indeed seems that it must be requiring someone to be intelligent and/or well-cultured individual. So why the change in the tones now? The reasons are that the actual intellectual class has degraded and cosints have replaced them, also too much theory and no connect with the real world has made them live in a simulacrum which is inhabited and endorsed by other cosints. And as we have seen above it is a perpetuating cycle, running especially in the universities (remember Taleb’s qualification). They theorize and jargonise (remember the buzzwords) simple concepts so much that no one who has got that special glossary will understand it). And cosints think it is how things should be. They write papers in education, supposedly for the betterment of the classroom teaching by the teachers, in such a manner that if you give it to a teacher, they will not be able to make any sense of it, leave alone finding something useful. Why? Because other cosints/IYI demand it! If you don’t write a paper in a prescribed format it is rejected, if it doesnt have enough statistics it is rejected, if it doesn’t give enough jargon in the form of theoretical review, and back scratching in the form of citations it is rejected. So what good are such papers which don’t lead to practice? And why should the teachers listen to you if you don’t have anything meaningful to tell them or something they don’t know already?

The noun to describe them:

sciolist – (noun) – One who engages in pretentious display of superficial knowledge.

Technologies in the classroom

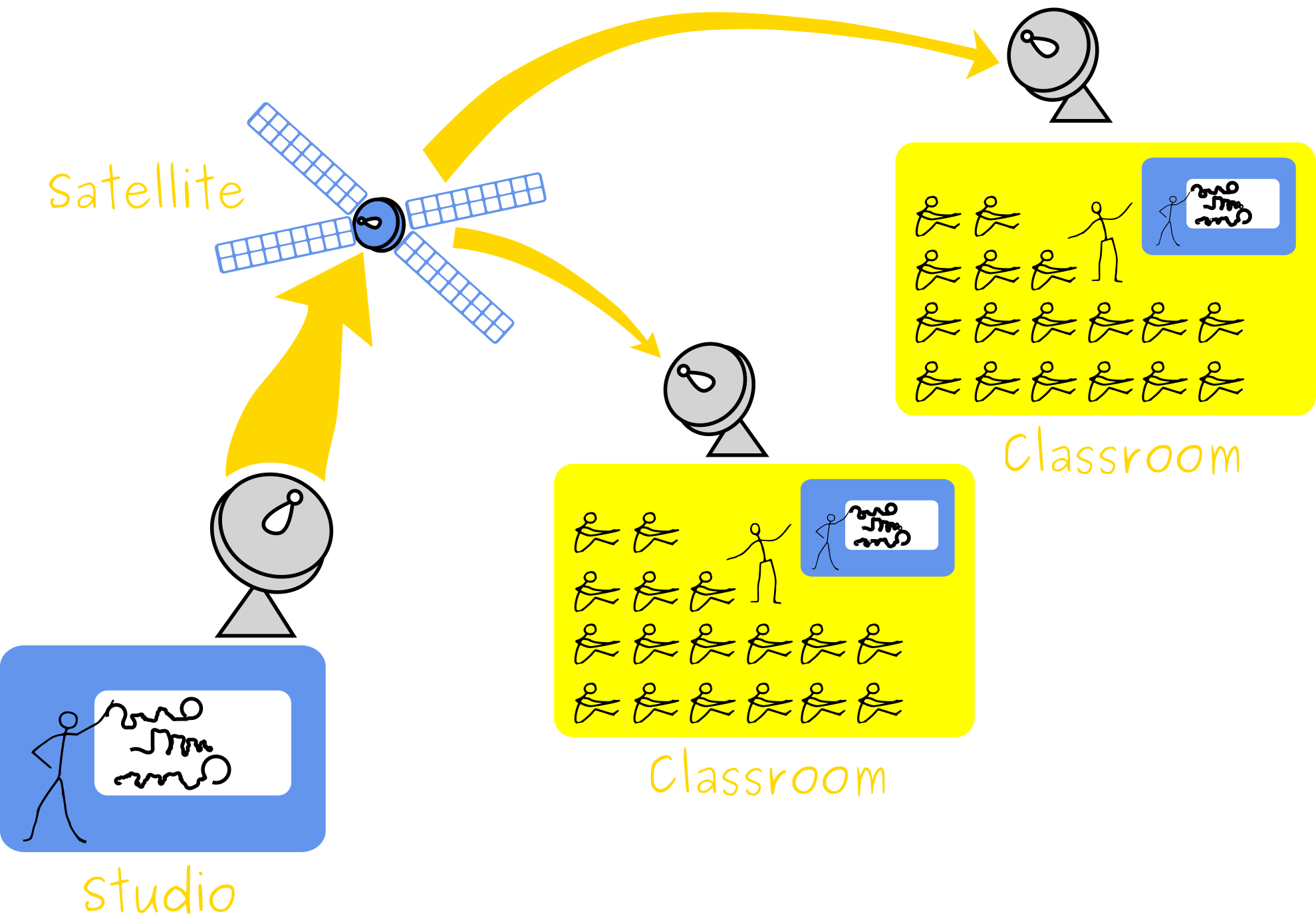

How to modernise education? How to make use of new technological developments that are around us to make learning in schools better? These are some of the questions that we will look at in the current post. In particular, we will be looking at the so-called satellite education as being implemented in some schools.

In many discussions regarding education, the teachers are usually blamed for not doing their assigned jobs correctly. There is some truth in these accusations. Having worked with teachers at different levels (primary to university) and in different settings (govt schools, private elite schools, teacher training institutes, colleges, and universities) I have come to the conclusion that teachers are part of the problem. This will be elaborated in another post and before you draw out your pitchforks the disclaimer: of course there are good teachers, who do their jobs well.

So one of the solutions is to take these good teachers to all the classrooms. Of course, it cannot be done in a physical way. This is where the technological advance pitches in. We take the good teachers to classrooms via satellites. The TV in the classroom becomes the blackboard, which allows the students to get the best of experiences that the system can offer. Now, this is not just limited to schools but also colleges, some of the best institutes in the country are offering “distance-education” courses like this. The government has invested a large sum in higher education in the form of Swayam channels. These channels are running lectures by various faculties of institutes across India 24×7. Mind you most of these are not specially produced lectures for the TV, they are recordings of usual lectures that these faculties give to their classes. Most are boring af, with them reading out the powerless-pointless slides one after other. They cram as much text as possible on these slides. Making them dense in terms of ink ratio, but unfathomable in terms of learning from them. Anyways this is a subject for another post.

Imagination and philosophies

Our sense of imagination is limited by what we know, and the

philosophies that we subscribe to. For some, it is clear about what their assumptions are for others it is not. They think that this is how it should be, completely ignorant of the notion that some of their concepts are based on assumptions. For some people, this is something that they are aware of, for most of us, we are not aware of this. Many

times we think of finding solace in things which are traditional. Since it has stood the test of time, it must have some inherent value they say. It is our ignorance and arrogance that we are not seeing any value in it. Hence people resist change. Why try something new which might or might work, or work equally well when we have something which is tried and tested? Of course, stability is important, but then stability does not lead to change. Yet when people change things, they try to replicate the models that they have found to work, and hence reducing the risk.

If we apply the same idea with regards to education, we also come across many such examples. The satellite television used in the classroom is one such case. The idea is not new. As soon as television technology became commonly feasible in the 50s and 60s, immediately some pedagogues of the era jumped to the idea of using them for education. This ideally suited the “transmission model” of education which was in vogue at that time with behaviorism ruling the roost of psychology in general and education in particular. In a way, learning via television is the ultimate epitome of the transmission model. In a regular classroom, there is at least a scope for the teacher and student to interact. But in this case, the entire flow of information is in one direction. The transmission is the transmission of learning. No wonder for many decades, and even now television was seen as a game-changer and harbinger of technological learning. Television was also seen as non-invasive technology, as it is passive which works for everyone involved, except perhaps for the most important stakeholders the learner. The television didn’t and doesn’t challenge the traditional “transmission model” of education, which most teachers and stakeholders (including parents) do believe in. The values which enlightened pedagogues worship, find a very low priority with most other stakeholders.

The central mindset in education

The term “centralised mindset” refers to the idea that in complex systems there has to be a controlling agent who overseas all executions. The centralised mindset refers to a belief that any system which works well must have a system or authority (in the form of a person or a group) which must somehow control the mechanism. The belief in the centralised mindset is that the individuals in a complex system are too unintelligent to behave in a coordinated, complex manner. For example, for a long time, it was believed that the “V” formation that one sees in the flying birds is due to a “leader” in the group. This supposed leader will make the group fall in the “V” patterns by organising the other group members. This is a very intuitive model that appeals to common sense. Whenever we see some patterns, we assume there must be an inherent design or a designer. In the case of the birds in “V” shape the same logic applies. There must be a leader who makes sure such a pattern is created. But such a view, however intuitive and correct it may seem is incorrect. As it happens with most of the other principles in science, in this case too the correct explanation is counter-intuitive. There is no leader in the case of the birds. The “V” pattern that we see is an example of what is known as an emergent phenomenon. It arises from the interaction of the birds which are flying together. When all the individuals follow simple rules in interacting with their neighbours, the “V” pattern emerges. The people who believe in a central leader are wrong in this case. It is a fiction that makes things that we observe easy to accept. But it is not correct. For many such examples and deeper discussions, see Turtles, Termites, and Traffic Jams by Mitchel Resnick.

There are several natural and artificial phenomena where earlier we (including the experts who propose such explanations) though that there was a central control involved in creating patterns, but in most cases, we have discovered otherwise. The counter-intuitive explanation that there is no central control or mechanism just doesn’t appeal to people. How can it be that there is no central control and yet the thing works on its own? Do we always need a centralised control? People argue that without a centralised control there will be chaos or anarchy. Stable patterns of behaviour or observations cannot emerge, it is assumed if there is no central control. Examples are given of a central governing that we are used to so much.

Now you might be wondering what has this to do with education? The general bureaucracy in the educational field is seen as centralised. For example, the creation of a textbook or syllabus or curriculum and assessment is always a centralised process. Think of the board exams.

Why cannot a school or a teacher decide upon textbooks and curriculum?

Why this is so? Because that is how it was in the other government departments. This is what the tradition says. A bunch of experts (preferably with a prefix of a Dr. or Prof.) will decide for everyone what they should learn and more importantly how they should learn it and most importantly how will this learning be assessed. This triumvirate or what to learn, how to learn and how to assess is assumed to be too complex and too important to be left to the plebs. This is where centralised mindset in the form of centralised expert committees is brought in.

The power of the teacher in the classroom is reduced to

a mere executioner ( a meek dictator if you will, as per Krishna Kumar) of all the algorithms set for them to follow. Some good teachers would improvise on this little elbow room that the classroom did offer. But now in an effort to make it

more central in discourse and execution, a centralised teacher and

teaching is needed. Indeed this is the idea behind the satellite television in the

classrooms. To ensure that quality (standardised) education reaches all learners. This also reduces the load on the local teachers, who just have to shepherd the learners to the AV room, and their job is done. The parents are happy as their children are supposed to be learning from the best teacher. And this happens live in some cases, I witnessed this entire process in Rajasthan. Seeing it from the studio being recorded and transmitted live via the satellite, and also saw (at another time) how it is received and executed in the schools. In some cases for interactivity and feedback, a Whatsapp number is provided where the teachers or the learners can reach out to the teacher in the studio. This teacher at the studio genuinely believed that he was being helpful to the students and the system worked. The proof for this was not some study but the messages he received from the school teachers thanking him for taking their class. Real interactivity which might happen in an actual classroom was found to be missing.

Just like the illustration on the top of the post shows, the core idea in the satellite television in the classroom is to centrally repeat the process of transmission of knowledge to all the learners with an added bonus of synchronicity. One act can be used at multiple locations. But this creates inhibitions for interactivity. Constructivism of the experts can go for a toss. Why do we need to create a custom curriculum for each child, when one expert in one manner can teach them all at the same time?

Genetics and human nature

Usually, in the discussion regarding human nature, there is a group of academics who would like to put all the differences amongst humans to non-genetic components. That is to say, the cultural heritage plays a much more important or the only important role in the transfer of characteristics. In the case of education, this is one of the most contested topics. The nature-nurture debate as it is known goes to the heart of many theories of human behaviour, learning and cognition. The behaviourist school was very strong until the mid 20th century. This school strongly believed that the entirety of human learning is dependent only on the environment with the genes or (traits inherited from the parents) playing little or no role. This view was seriously challenged on multiple fronts with attacks from at least six fields of academic inquiry: linguists, psychology, philosophy, artificial intelligence, anthropology, and neuroscience. The advances in these fields and the results of the studies strongly countered the core aspects of behaviourism. Though the main thrust of the behaviourist ideas seems to be lost, but the spirit still persists. This is in the form of academics who still deny any role for genes, or even shun at the possibility of genes having any effect on human behaviour. They say it is all the “environment” or nurture as they name it. Any attempt to study the genetic effects are immediately classified as fascist, Nazi or equated to social Darwinism and eugenics. But over several decades now, studies which look at these aspects have given us a mounting mountain of evidence to lay the idea to rest. The genes do play a definitive role and what we are learning is that the home environment may not be playing any role at all or a very little role in determining how we turn out. Estimates range from 0 to 10%. The genes, on the other hand, have been found to have about 50% estimate, the rest 40% being attributed to a “unique” environment that the individual experiences. Though typically, some of the individuals in academia argue strongly against the use of genetics or even mention of the word associated with education or any other parameters related to education. But this has to do more with their ideological positions, which they do not want to change, than actual science. This is Kuhnian drama of a changing science at work. The old scientists do not want to give up on their pet theories even in the case of evidence against them. This is not a unique case, the history of science is full of such episodes.

Arthur Jensen, was one of the pioneers of studying the effect of genetic heritability in learning. And he lived through the behaviourist and the strong nurture phases of it. This quote of his summarises his stand very well.

Racism and social elitism fundamentally arise from identification of individuals with their genetic ancestry; they ignore individuality in favor of group characteristics; they emphasize pride in group characteristics, not individual accomplishment; they are more concerned with who belongs to what, and with head-counting and percentages and quotas than with respecting the characteristics of individuals in their own right. This kind of thinking is contradicted by genetics; it is anti-Mendelian. And even if you profess to abhor racism and social elitism and are joined in battle against them, you can only remain in a miserable quandary if at the same time you continue to think, explicitly or implicitly, in terms of non-genetic or antigenetic theories of human differences. Wrong theories exact their own penalties from those who believe them. Unfortunately, among many of my critics and among many students I repeatedly encounter lines of argument which reveal disturbing thought-blocks to distinguishing individuals from statistical characteristics (usually the mean) of the groups with which they are historically or socially identified.

– Arthur Jensen, Educability and Group Differences 1973

As the highlighted sentence in the quote remarks, the theories which are wrong or are proven to be wrong do certainly exact penalties from their believers. One case from history of science being the rise and rise of Lysenkoism in the erstwhile USSR. The current bunch of academics who strongly deny any involvement of genes in the theories of human learning are no different.

The logician, the mathematician, the physicist, and the engineer

The logician, the mathematician, the physicist, and the engineer. “Look at this mathematician,” said the logician. “He observes that the first ninety-nine numbers are less than hundred and infers hence, by what he calls induction, that all numbers are less than a hundred.”

“A physicist believes,” said the mathematician, “that 60 is divisible by all numbers. He observes that 60 is divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. He examines a few more cases, as 10, 20, and 30, taken at random as he says. Since 60 is divisible also by these, he considers the experimental evidence sufficient.”

“Yes, but look at the engineers,” said the physicist. “An engineer suspected that all odd numbers are prime numbers. At any rate, 1 can be considered as a prime number, he argued. Then there come 3, 5, and 7, all indubitably primes. Then there comes 9; an awkward case, it does not seem to be a prime number. Yet 11 and 13 are certainly primes. ‘Coming back to 9’ he said, ‘I conclude that 9 must be an experimental error.'”

– George Polya (Induction and Analogy – Mathematics of Plausible Reasoning – Vol. 1, 1954)

On mathematics

Mathematics is regarded as a demonstrative science. Yet this is only one of its aspects. Finished mathematics presented in a finished form appears as purely demonstrative, consisting of proofs only. Yet mathematics in the making resembles any other human knowledge in the making. You have to guess a mathematical theorem before you prove it; you have to guess the idea of the proof before you carry through the details. You have to combine observations and follow analogies; you have to try and try again. The result of the mathematician’s creative work is demonstrative reasoning, a proof; but the proof is discovered by plausible reasoning, by guessing. If the learning of mathematics reflects to any degree the invention of mathematics, it must have a place for guessing, for plausible inference.

– George Polya (Induction and Analogy – Mathematics of Plausible Reasoning – Vol. 1, 1954)

Unreal and Useless Problems

We had previously talked about problem with contexts given in mathematics problems. This is not new, Thorndike in 1926 made similar observations.

Unreal and Useless Problems

In a previous chapter it was shown that about half of the verbal problems given in standard courses were not genuine, since in real life the answer would not be needed. Obviously we should not, except for reasons of weight, thus connect algebraic work with futility. Similarly we should not teach the pupil to solve by algebra problems which in reality are better solved otherwise, for example, by actual counting or measuring. Similarly we should not set him to solve problems which are silly or trivial, connecting algebra in his mind with pettiness and folly, unless there is some clear, counterbalancing gain.

This may seem beside the point to some teachers, ”A problem is just a problem to the children,” they will say,

“The children don’t know or care whether it is about men or fairies, ball games or consecutive numbers.” This may be largely true in some classes, but it strengthens our criticism. For, if pupils^do not know what the problem is about, they are forming the extremely bad habit of solving problems by considering only the numbers, conjunctions, etc., regardless of the situation described. If they do not care what it is about, it is probably because the problems encountered have not on the average been worth caring about save as corpora vilia for practice in thinking.

Another objection to our criticism may be that great mathematicians have been interested in problems which are admittedly silly or trivial. So Bhaskara addresses a young woman as follows: ”The square root of half the number of a swarm of bees is gone to a shrub of jasmine; and so are eight-ninths of the swarm: a female is buzzing to one remaining male that is humming within a lotus, in which he is confined, having been allured to it by its fragrance at night. Say, lovely woman, the number of bees.” Euclid is the reputed author of: ”A mule and a donkey were going to market laden with wheat. The mule said,’If you gave me one measure I should carry twice as much as you, but if I gave you one we should bear equal burdens.’ Tell me, learned geometrician, what were their burdens.” Diophantus is said to have included in his preparations for death the composition of this for his epitaph : ” Diophantus passed one-sixth of his life in childhood one-twelfth in youth, and one-seventh more as a bachelor. Five years after his marriage was born a son, who died four years before his father at half his father’s age.”

My answer to this is that pupils of great mathematical interest and ability to whom the mathematical aspects of these problems outweigh all else about them will also be interested in such problems, but the rank and file of pupils will react primarily to the silliness and triviality. If all they experience of algebra is that it solves such problems they will think it a folly; if all they know of Euclid or Diophantus is that he put such problems, they will think him a fool. Such enjoyment of these problems as they do have is indeed compounded in part of a feeling of superiority.

– From Thorndike et al. The Psychology of Algebra 1926

School as a manufacturing process

Over most of this century, school has been conceived as a manufacturing process in which raw materials (youngsters) are operated upon by the educational process (machinery), some for a longer period than others, and turned into finished products. Youngsters learn in lockstep or not at all (frequently not at all) in an assembly line of workers (teachers) who run the instructional machinery. A curriculum of mostly factual knowledge is poured into the products to the degree they can absorb it, using mostly expository teaching methods. The bosses (school administrators) tell the workers how to make the products under rigid work rules that give them little or no stake in the process.

– (Rubba, et al. Science Education in the United States: Editors Reflections. 1991)