So said one of the founders quantum mechanics Max Planck. But I think this quote applies to other areas of human endeavour as well. I have been working in the area of learning for major part of my adult life. During my own learning, when computers were just getting mainstream (late 1990s and early 2000s) I experienced first-hand how learning experience can be enhanced by proper use of computers. Another aspect of proliferation of computer which are connected to the internet is that you have access to sum of almost all human knowledge available to you. Even 20 years back this was not the case. I remember when I discovered that there are accessible resources about physics on the web, it was almost a revelation. And the resources grow day-by-day, becoming more and more accessible to everyone. Even with a smartphone you can access all the information on the web. Most modern web designers are adopting a mobile first policy.

I have been musing about these impacts on learning experience ever since. But there is a strong opposition to use technology in the classroom. This mostly comes from people in two categories. One is a old lot who grew and learned in a world without accessible technology and other is a younger lot who have weird (read extremist) ideas about teaching and learning. The younger lot is a lost tribe who live on the Eastern pole. Both these two categories of people opposed to use of technology in the classroom think that they are “progressive” and are fighting against “oppressive” technology.

A note on the term “technology”: Here I am using the term “technology” in a narrow sense of computer technology. A more inclusive sense would include blackboards, printed textbooks and the classroom itself as forms of technology.

I will try to present this perspective of opposition to technology in classroom and dismantle them giving a rebuttal. In some cases, the holders of these ideas are beyond redemption, and quote of the Max Planck which is the title of the post applies to them. They will die off and their technophobia will die with them. A newer generation of pedagogues conversant and comfortable with technology will emerge in the next generation and will be in tune with the need of the time.

Let us start with the older lot. Many of the progressive pedagogues grew in India that was deprived of any computer technology. This was the era of many socialist inspired people’s movement which aspired for egalitarian approach to education, particularly the sections of society which are low in socio-economic order. The approach was to enlighten the masses inspired from the socialist ideas. Now till 90s, the computer technology was expensive and its use even in the developed countries was rather limited. And most of the people in the older lot I am talking about did spend their formative and working years in this era.

Now it is not to say that all of the people did not have any contact with computers at all. Some of these inspired people were highly qualified individuals who did their research work in some of the best institutions in the world. Some of them had some experience of using the computers. But computers were never a second nature to them, as they are not to many people even now. And a lot of them never used computer, because in their era it was an expensive technology and hence they didn’t have access to it. Hence it made computer technology an alien artefact for them in that era.

And when computers finally became accessible, their own years of learning new things had long gone by. Some of them did adopt newer computer technology, able to see the potential to transform both learning and dissemination of knowledge, but most didn’t. Apart from the ideological commitment to a “non-computer” approach to learning, I think their own fears and phobia of being unable to learn and use the new technology also played a role in their opposition. This was the situation in early 2000s, which was still acceptable as computer and internet penetration was not good. These pedagogues threw anything to do with computers as too Western (hence sitting on Eastern pole from where every direction is West).

But by 2010, smart phones were becoming more and more common as were the desktop computers and laptops. By 2015, the access to cheap smart phones with fast internet exploded. Now, here were are in the mid 2020s when proliferation of computer devices in the form of smartphones, tablets and laptops is increasing by the day. The dreams of last mile connectivity are not far off.

The Covid-19 pandemic forced us to shift to online classes. Of course, it did have its issues particularly for students who lacked infrastructure in terms of devices and connectivity. But it did show that even with present conditions something is still possible. Yet, people had their doubts. Now its been

Yet, the resistance from the older pedagogues continues. They cannot get away from ideas about computers that were formed 4 decades back, when computers were still primitive and expensive. And they continue to the same arguments even today. Questions like “Have computers reached everyone?” and since they have not we cannot use them. Or they give overarching statements like “The most downtrodden will be neglected in this”. They are like classical physicists who could not accept ideas of modern physics at the turn of the last century.

To objections like these, I have two rebuttals, one is historical-pedagogical and other is on the nature of computer technology in particular. Let us look at the first objection: “Have computers reached everyone?”, of course, they have not! But what about other technologies like the classroom and blackboard? Yes they are technologies! Have they reached everyone? Of course not! But then you don’t give the same arguments, let school reach every child (or every child reach the school) and only then we will allow/accept school as a viable mechanism for learning. And that is something they will never accept, just because they are comfortable/conversant with technology school-classroom-black-board-textbooks. That is a given for them. But even that “technology” has access issues, and comes loaded with challenges of its own for learning. I mean these are the very challenges that many of these pedagogically oriented movements addressed.

So this argument about last-mile connectivity applies to the existing technologies to teaching and learning as well. Why should it be singled out for “computer” technology? This is only because the older lot is not familiar (rather don’t want to accept) with the potential of the computer technology as it would destroy their anachronistic cherished notions of teaching and learning.

Other major assumption in this notion is that the teacher and textbook are the (sometimes the only) source of knowledge, almost an axiom in the Euclidean sense.

Is this why there was so much focus on developing text-based teaching learning materials. But this is no longer true. We now have almost entire sum of human knowledge accessible literally at fingertips to anyone with a connected device. But now with Open Education and internet this is being challenged in a serious way. Added to this is the absolutely disruptive technology of AI bots like chatGPT. Why should learning be limited to a centralised textbook which usually does not take into account the context of learners written by folks sitting in ivory towers, which is not updated for years?

Now we have the technology and appropriate legal licenses to change this by really empowering learners to bypass the filters of textbooks and teachers. But still we are hung on cherished notion of teacher in the constructivist classroom.

Now, I come to aspects of the nature of technology and young learners. The nature of “computer” technology is such that younger learners adapt to it very quickly. They are still in the phase of learning about the world. A very young child given a smartphone will try out everything and figure out how it works (or doesn’t) and start playing with it as if its any other toy. Parents often ask help from their very young children to solve technological challenges they face.

Same is true for teachers. I have seen enough examples during my field work in very rural areas. Learners when exposed to computer technology even for a very short time several were first-generation learners who were using computer for the first time, could out-pace the teacher in using the computer for the task at hand. Now in the traditional approach (even the progressive ones) the knowledge of teacher is almost never surpassed in a teaching-learning setting. The teacher is always the “more-able-peer” in the Vygotskian sense and is considered as an a priori truth. Now, I am not denying that in many senses this is correct, but if you give access to technology to young learners in many cases the need for teacher is bypassed. This is in the true sense that a child constructs knowledge with the only difference being that it is not mediated by the teacher (or even if it is teacher is exactly a mediator). Constructionist microworlds provide excellent examples of such learning by the learners on their own. By denying access to computer technology, this is what is being missed.

Of course there are examples and examples of bad use of technology in the form of PPT/click books etc which is often rightfully criticised. But that is missing forest of the trees. Another point in this regard is that educational technology abhors vacuum, if any technology is not opted by good pedagogy, it will be co-opted by a bad one. So we need to stake claim, otherwise poor pedagogical approaches which just replicate what is done without a computer to be done on a computer. To give Papert’s analogy it would be like attaching a jet engine to a horse-wagon!

Now we come to the younger lot. They typically have grown with technology in their formative years. And as reasearchers and activists they use computers and internet and are familiar with the technologies. Yet they give the same arguments of “oppression” as the older lot. I mean it doesn’t occur to them they are using the same computers for their own work because it suits them. But when it comes to use in the classroom it is not to be used. Double standards much. If they think the computers are oppressive as much, they should stop using it themselves. But then how will they post social media updates on Facebook and Twitter?

The younger generation of people who oppose technology in the classroom fits very well in the category of people without skin in the game (after Taleb). For things they think computer is useful for themselves, they will make full use of it be it data analysis, report writing or other work. But they are not ready to give same concession to children (especially in resource deprived areas) who need such scaffolding more. Instead they want to deprive the children of a learning companion because it does not work with their ideological world view centred at Eastern pole. And some of these same researchers, when it comes to their own children will provide them with computers and tablets for learning. But when it comes to the children who need it more…

I could go on and on.. But you get the point, the opposition is not based on factual aspects but ideological and there too they are on thin ice. But the opposition is waning funeral by funeral and computers are the new normal…

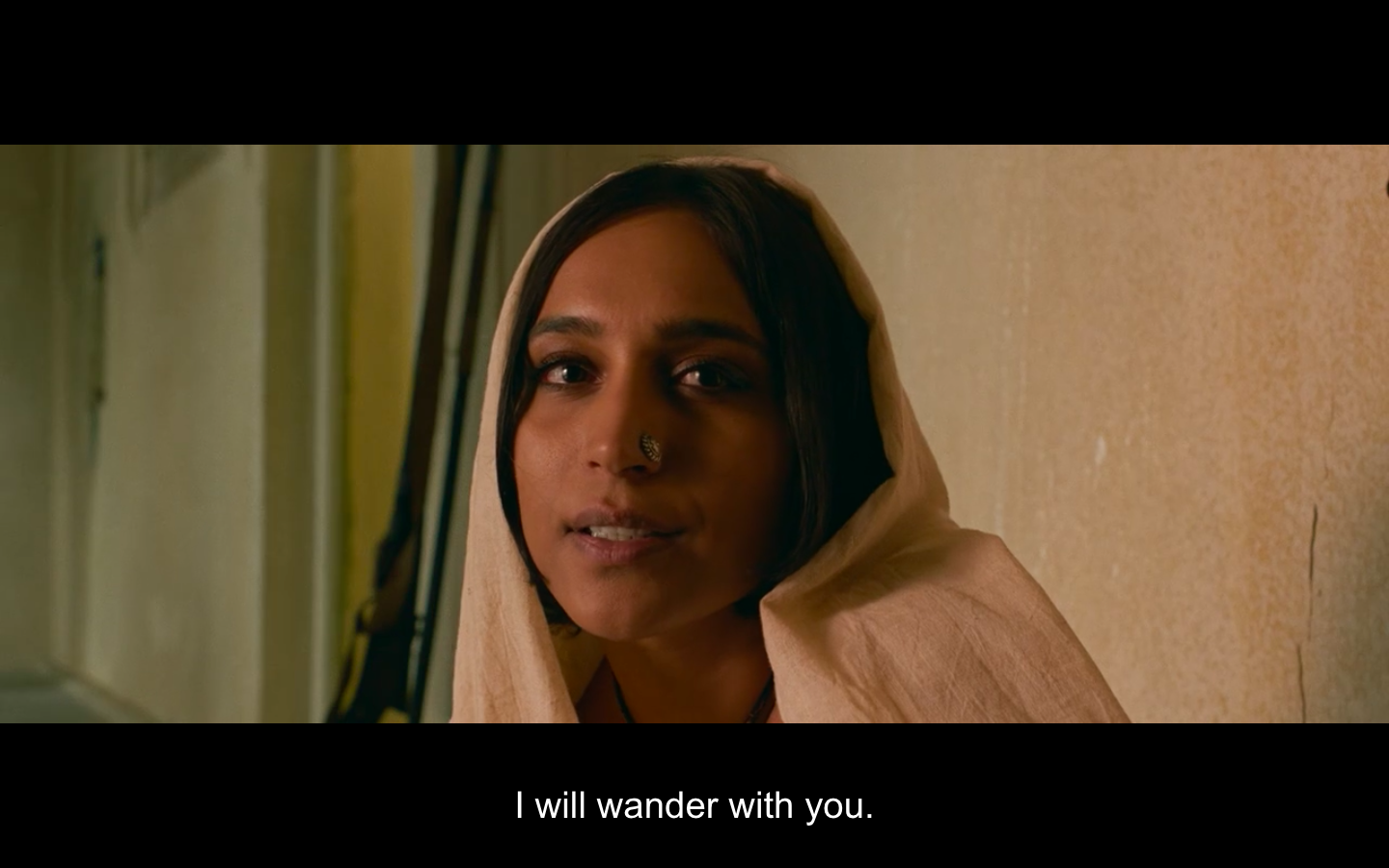

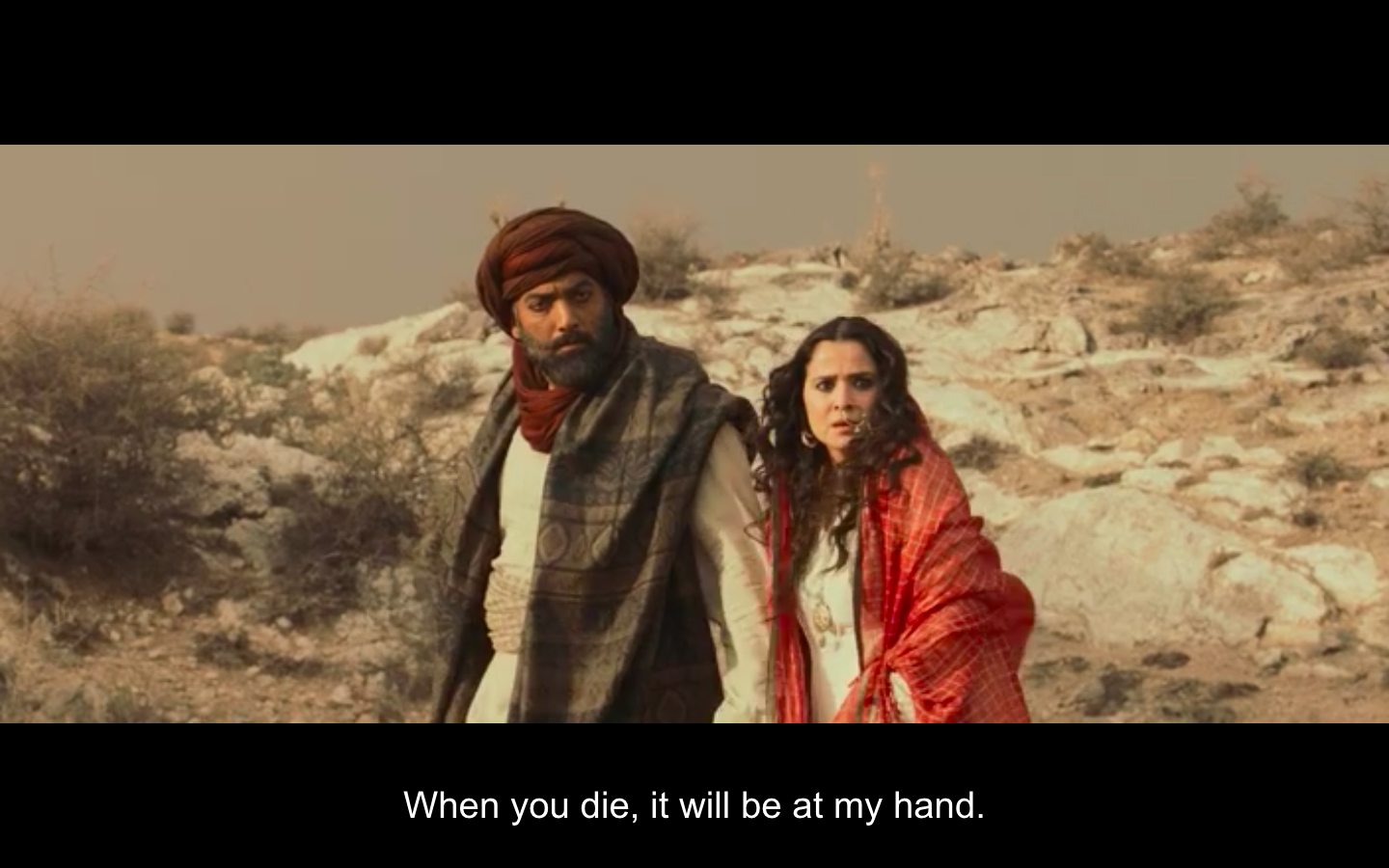

The character has no name in the film, but he finds people who are wanted for a price. That is how he makes his living. He refuses a horse mount saying it interferes with His character has many layers and he shares a special relationship with the Gossain, they respect each other. It was a treat to watch Dobriyal play this character with English hat and his greeting of:

The character has no name in the film, but he finds people who are wanted for a price. That is how he makes his living. He refuses a horse mount saying it interferes with His character has many layers and he shares a special relationship with the Gossain, they respect each other. It was a treat to watch Dobriyal play this character with English hat and his greeting of: